A Ballad of Bruised Pride and Unyielding Survival in a Restless World

When “The Boxer” by Bob Dylan was released as a single in March 1969, it quietly entered the charts at a turbulent moment in American history—and yet its impact was anything but quiet. The song reached No. 7 on the U.S. Billboard Hot 100 and climbed even higher in the United Kingdom, peaking at No. 6 on the UK Singles Chart. It would later appear on the landmark album Self Portrait (1970), but its true life began as a standalone single, standing apart in both structure and spirit from much of Dylan’s late-1960s catalog.

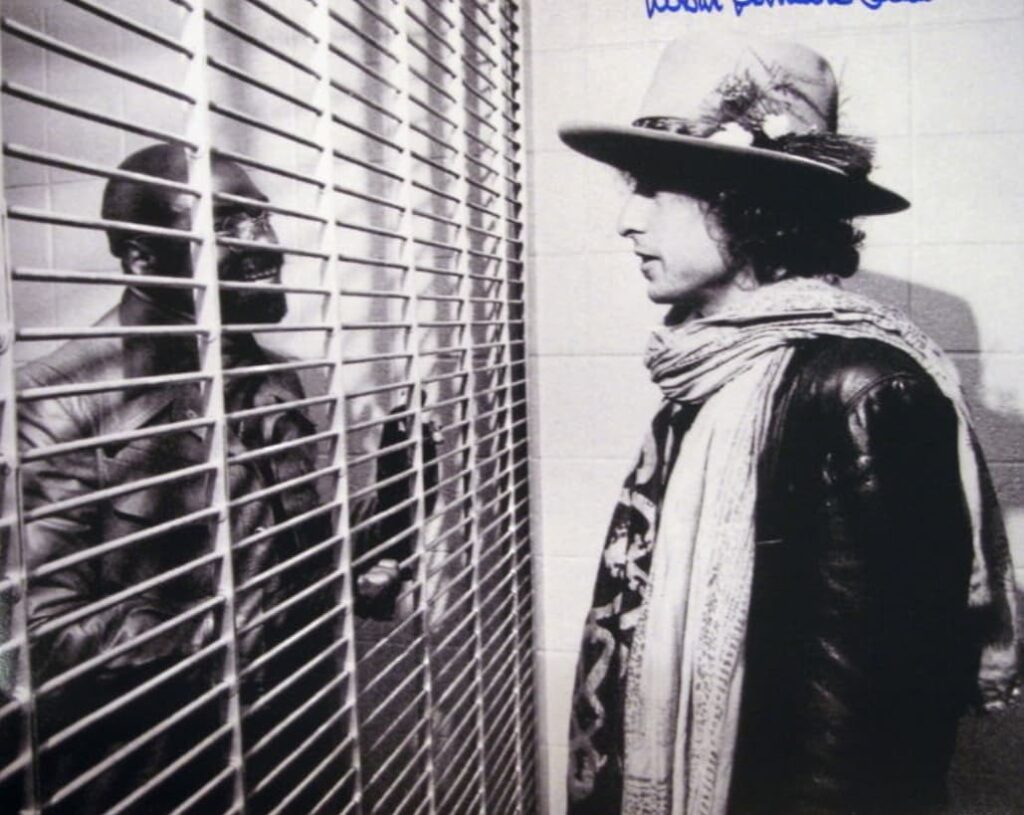

From the very first verse—“I am just a poor boy, though my story’s seldom told”—the song feels less like a performance and more like a confession whispered across time. By 1969, Bob Dylan was already a cultural lightning rod, a figure alternately revered and misunderstood. Having electrified folk music at the Newport Folk Festival just a few years earlier and weathered both praise and backlash, Dylan himself seemed not unlike the battered protagonist of his own song: wounded by public scrutiny, yet stubbornly standing.

The arrangement of “The Boxer” is one of its most haunting features. That echoing, almost liturgical “lie-la-lie” refrain is no mere ornament. It acts as a Greek chorus, a sigh between verses, a wordless acknowledgment of pain that language alone cannot carry. Producer Bob Johnston helped shape the track’s stark but spacious sound, recorded in Nashville and later in New York. The percussion—especially that thunderous snare drum crack recorded in Columbia’s Studio A—lands like a blow in the ring. Each strike feels symbolic, a reminder of the physical and emotional bruises life inflicts.

Lyrically, the song tells the story of a young man who leaves home, faces loneliness and exploitation in the city, and ultimately stands alone in the winter cold, “in the clearing stands a boxer.” Whether we interpret him as a literal fighter or as a metaphor for the artist, the worker, the dreamer, the immigrant, or even Dylan himself, the image resonates deeply. The boxer’s refusal to lie down—“Still I remain”—becomes the moral center of the piece. It is not triumph in the traditional sense. There is no roaring victory. There is endurance. And sometimes, endurance is the greater courage.

It is worth noting that Dylan wrote the song during a period of relative withdrawal from public life. After his 1966 motorcycle accident and the intense touring years with The Hawks (later known as The Band), he had retreated from the relentless spotlight. In that context, “The Boxer” can be heard as a quiet self-portrait—more intimate than grand, more human than heroic.

Over the decades, the song has been embraced by other artists who recognized its timeless quality. Most famously, Simon & Garfunkel released their own “The Boxer” in 1969 on the album Bridge Over Troubled Water, which became a massive international hit, reaching No. 7 in the U.S. and No. 6 in the UK as well. Though often associated with that duo’s crystalline harmonies, Dylan’s interpretation remains more weathered, more earthbound—a man telling his story without polish.

The meaning of “The Boxer” unfolds slowly. It speaks of alienation, pride, stubborn resilience, and the cost of holding onto one’s dignity in a world that offers little mercy. The city in the song is cold and impersonal. Work is scarce. Companionship is fleeting. Yet the central figure does not surrender his identity. There is something profoundly moving about that image of a solitary figure in the winter, refusing to collapse despite the blows.

Listening to the song today, one hears more than just a folk ballad from 1969. One hears the echo of countless private battles fought quietly and without applause. Bob Dylan, in his understated way, gave voice to that struggle—not with bombast, but with restraint and poetic clarity.

In the end, “The Boxer” endures because it understands something essential about the human spirit: that survival is rarely glamorous, rarely easy, but always worthy of song.