A Quiet Prayer for Ordinary Lives, Sung by Two Kindred Souls Across Time

When “Angel From Montgomery” first appeared in 1971, it did not announce itself as a hit, nor did it climb the charts with urgency or spectacle. Written and recorded by John Prine for his self-titled debut album John Prine (1971), the song never became a conventional chart success at the time of its release. It did not enter the Billboard Hot 100, and it was never designed to. Yet, over the decades, it has proven something far rarer than a hit record: it has become a permanent companion to generations who recognize their own quiet longings within its lines.

Placed early in Prine’s catalog, “Angel From Montgomery” immediately revealed the uncommon depth of his songwriting. Barely in his mid-twenties, Prine wrote from the perspective of a middle-aged woman trapped in domestic routine, spiritual fatigue, and emotional resignation. The narrator is not dramatic or bitter; she is tired, reflective, and painfully aware of time slipping away. That act of imaginative empathy was, and remains, extraordinary. Few songwriters—especially young men—have written so convincingly from outside themselves, and fewer still have done so with such restraint and compassion.

The song gained a second life in 1974 when Bonnie Raitt recorded it for her album Streetlights, which reached No. 25 on the Billboard 200. Though her version was not a major singles hit, it became definitive. Raitt did not reinterpret the song; she inhabited it. Her voice carried the weight of years, even then—weathered, intimate, and emotionally precise. Where Prine’s original felt observational, Raitt’s reading felt lived-in. From that point forward, “Angel From Montgomery” ceased to belong solely to its writer and became part of the shared American songbook.

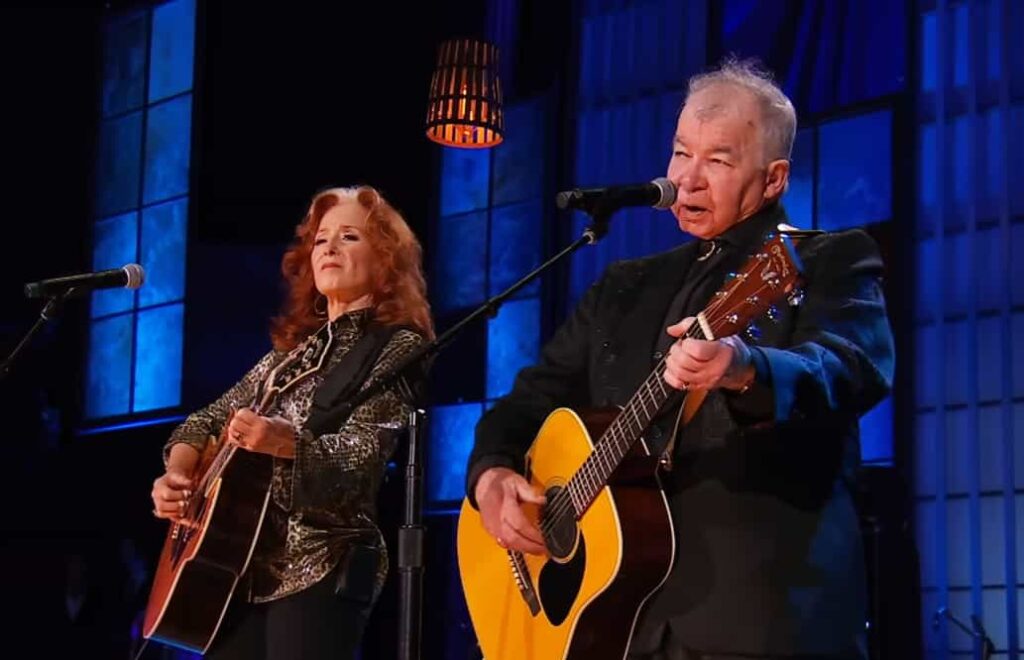

The song’s most moving chapter arrived in 1985, when Bonnie Raitt and John Prine performed “Angel From Montgomery” together at a concert held in tribute to Steve Goodman, their close friend and fellow songwriter, who had died the year before. Goodman was instrumental in Prine’s early career and deeply woven into the same folk tradition that valued truth over polish. On that stage, the duet carried more than melody—it carried absence. Prine and Raitt sang not only as collaborators, but as survivors honoring someone who had once stood between them, laughing, writing, believing in songs.

Musically, “Angel From Montgomery” is disarmingly simple. Its chord progression is plain, almost conversational, allowing the lyric to breathe. There is no theatrical climax, no soaring resolution. Instead, the song moves like thought itself—circling memory, regret, and fleeting hope. Lines such as “How the hell can a person go to work in the morning / And come home in the evening and have nothing to say” resonate more deeply with age, not less. They are questions asked quietly, perhaps too late, and that is why they endure.

What gives the song its lasting power is its refusal to judge its narrator. There is no irony, no distance, no cleverness. Prine offers dignity to a life often overlooked, and Raitt amplifies that dignity with warmth and gravity. Together, especially in their 1985 performance, they turn the song into something communal—a shared acknowledgment of roads not taken, love that settled into habit, and dreams that never entirely died.

In the end, “Angel From Montgomery” is not about escape. It is about recognition. It reminds listeners that longing does not vanish with age; it simply learns to whisper. That whisper, carried by John Prine’s pen and Bonnie Raitt’s voice, remains one of the most humane and enduring sounds in American music history.