“Honey Don’t” stands as a quiet but enduring testament to the playful heart of early rock and roll, where simplicity, rhythm, and human warmth mattered more than spectacle.

Released in December 1956, “Honey Don’t” arrived not as a headline-grabbing single, but as the B-side to “Blue Suede Shoes”, the record that would permanently inscribe Carl Perkins into music history. While “Blue Suede Shoes” surged to No. 2 on the Billboard Hot 100, topped the country chart, and crossed over to No. 1 on the R&B chart, “Honey Don’t” quietly rode along, initially overlooked yet never insignificant. Its placement on the flip side did not reflect a lack of quality, but rather the brutal economy of attention in the mid-1950s record industry, where even strong songs could be eclipsed by a cultural phenomenon.

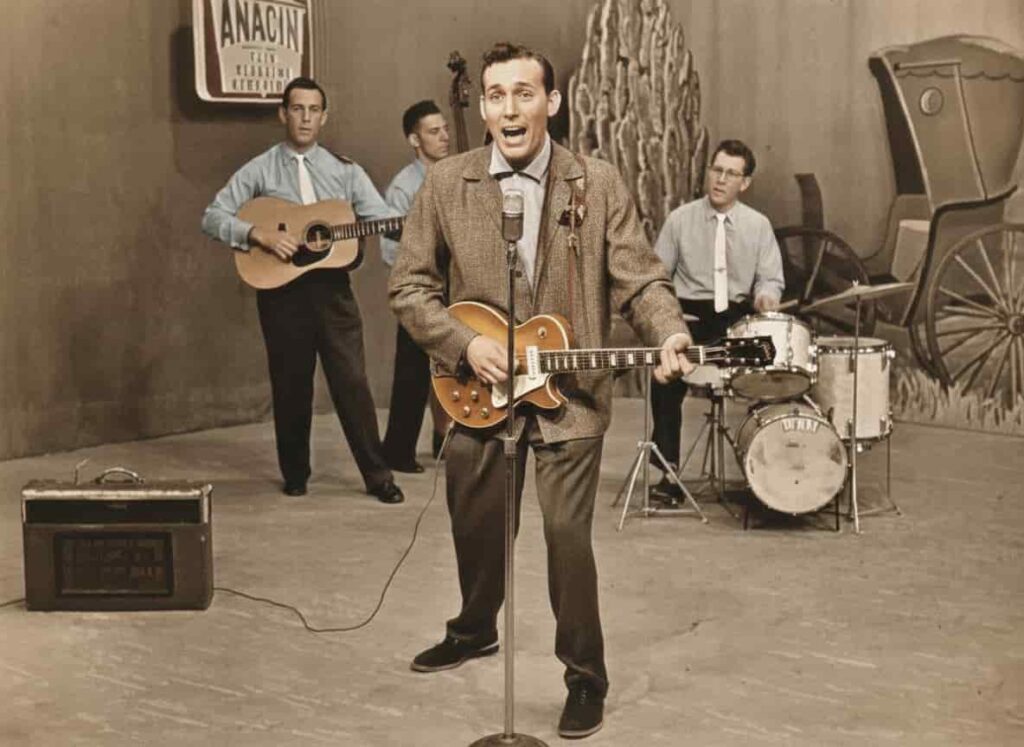

Recorded at Sun Studio in Memphis under the watchful ear of Sam Phillips, the song captures the very DNA of rockabilly at its most authentic. There is no excess here. No ornamentation. Just a tight rhythm section, Perkins’ unmistakable guitar style, and a voice that sounds as though it belongs to the back roads and front porches of the American South. Carl Perkins, already a master of merging country storytelling with the pulse of emerging rock and roll, understood restraint as well as drive. That balance is precisely what gives “Honey Don’t” its lasting charm.

Lyrically, the song is disarmingly simple. A man addresses his lover with a gentle warning, half teasing, half sincere. The phrase “Honey, don’t” is repeated not as a command, but as an appeal, rooted in affection rather than control. In an era when rock and roll was often associated with rebellion and bravado, Perkins offered something quieter and more human. His Southern drawl, unpolished and honest, gives the song an intimacy that feels conversational, as if overheard rather than performed.

Musically, “Honey Don’t” is a textbook example of Perkins’ guitar language. The rhythm is buoyant, driven by a clean, percussive strum that locks perfectly with the backbeat. There is swing in the groove, but also discipline. Every note serves the song. This approach would become deeply influential, particularly among British musicians studying American records with near-religious devotion in the early 1960s.

That influence became fully visible when The Beatles recorded “Honey Don’t” in 1964 for their album “Beatles for Sale.” Sung by Ringo Starr, their version preserved the song’s playful spirit while introducing it to a new generation across the Atlantic. Released in the UK as the B-side to “Everybody’s Trying to Be My Baby,” the single reached the Top 10 of the UK Singles Chart, bringing renewed attention to Perkins’ original work. For many listeners, this cover served as a gateway back to the Sun Records catalog and to the foundational figures of rock and roll.

In retrospect, “Honey Don’t” represents something essential about Carl Perkins’ legacy. It reminds us that not every important song arrives as a chart-topper or a cultural earthquake. Some endure because they capture everyday emotion with honesty and musical economy. For listeners who lived through the 1950s, the song recalls a time when records were short, direct, and deeply personal. For those who discovered it later, it offers a window into the values that shaped the earliest days of rock and roll.

Today, “Honey Don’t” remains a small but vital thread in the larger fabric of popular music history. It is a song that does not shout its importance, yet continues to speak, softly and clearly, to anyone willing to listen.