A Toast of Regret and Redemption in a Texas Honky Tonk Glass

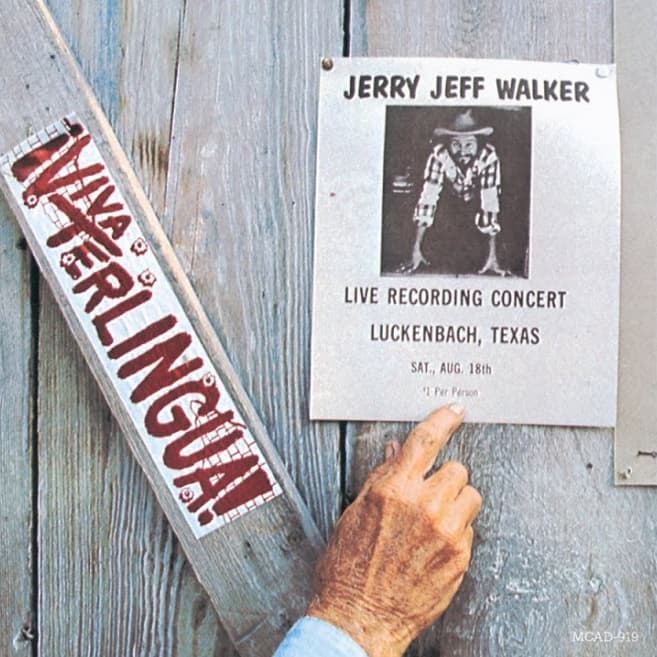

When Backslider’s Wine appears on ¡Viva Terlingua!, the live and now-legendary 1973 album by Jerry Jeff Walker and The Lost Gonzo Band, it emerges not as a footnote but as one of the record’s most quietly devastating moments. Released in 1973 under MCA Nashville, ¡Viva Terlingua! charted modestly at #160 in the United States, yet its cultural influence would later grow far beyond its commercial performance. Within this iconic collection of Texas storytelling and outlaw spirit, “Backslider’s Wine” occupies a place of intimate gravity. Though written by Michael Martin Murphey rather than Walker himself, its inclusion speaks volumes about Walker’s singular gift for choosing songs that mirrored the fragile, whiskey-stained corners of the human experience.

Recorded in Luckenbach, Texas in August of 1973, the sessions for ¡Viva Terlingua! relied on atmosphere rather than polish. The creaky dancehall floorboards, the dim glow of stage lights, and the hum of a small but loyal crowd formed the true acoustic shell around the music. It was an environment where honesty mattered more than precision, and “Backslider’s Wine” is perhaps the clearest portrait of that ethos. The song does not try to impress. It tries to confess.

The lyrics unfold like a weary whisper at closing time. “Face down on the barroom floor,” the narrator is not simply drunk but spiritually unmoored. The wine becomes a symbol of all the slips and stumbles that accumulate across a life. It is the drink of those who have drifted from the better angels of their nature. The recurring memory of a mother’s warning, “Don’t drink Backslider’s wine,” hangs like a soft bell of conscience that keeps ringing long after the glass is empty. The simplicity of these lines is deceptive; beneath them lies a landscape of regret, longing, and the unsteady hope that tomorrow might be gentler.

Musically, the arrangement is deliberate and restrained. Acoustic guitar sits at the center, joined by modest touches of steel and harmonica. Nothing intrudes. Nothing distracts. The spare instrumentation creates space for the listener to inhabit the emotional room of the song. It feels less like a performance and more like a shared moment between strangers who recognize the same ache.

Within the broader arc of country music’s shift toward authenticity during the early 1970s, “Backslider’s Wine” became more than a track on a beloved album. It became a quiet testament to the power of truth told without ornament. Through Walker’s weathered voice, the song still offers what it offered in 1973: a moment to look inward, to acknowledge the stumbles behind us, and to imagine, however faintly, the possibility of redemption ahead.