A Tenderly Ironic Farewell to Country Pride and Heartache

Few songs in the American country canon balance satire and sincerity as gracefully as “You Never Even Call Me By My Name.” Written by Steve Goodman and John Prine, and immortalized by David Allan Coe, the song was released in 1975 and climbed to No. 8 on the Billboard Hot Country Singles chart in early 1976. It later appeared on Coe’s album Once Upon a Rhyme (1975). Though often remembered as a humorous anthem, its roots lie in the sharp wit and poetic sensibility of two of the most literate songwriters of their generation—Prine and Goodman—both deeply connected to the Chicago folk scene of the late 1960s and early 1970s.

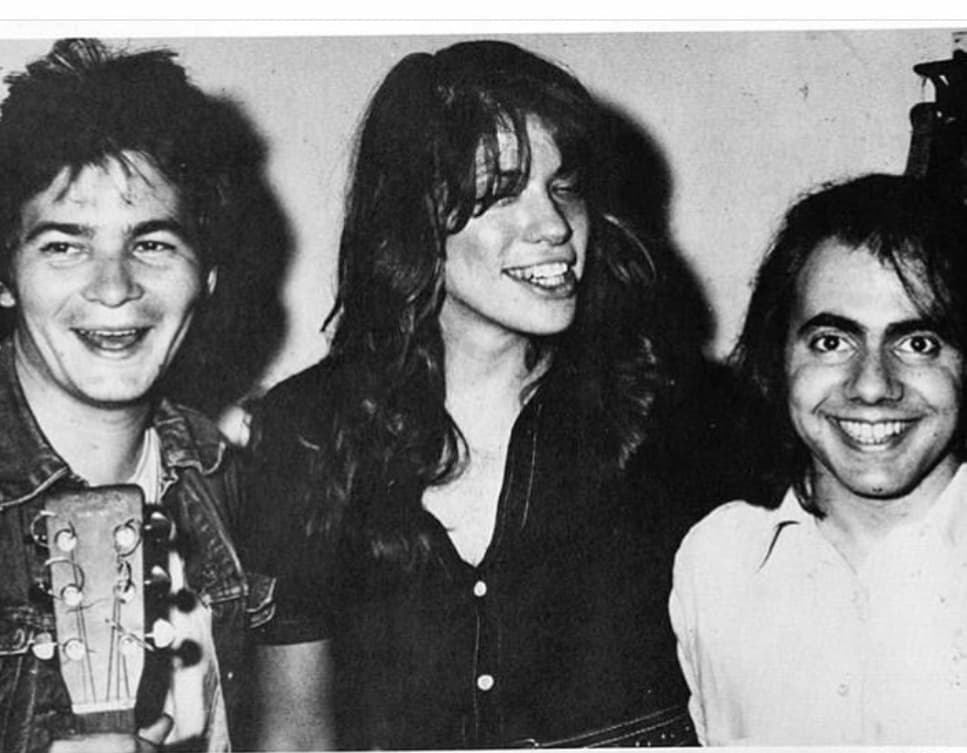

The story behind the song is as charming as the song itself. Steve Goodman, best known for “City of New Orleans,” co-wrote “You Never Even Call Me By My Name” with his close friend John Prine. They initially conceived it as a playful parody of formulaic country songwriting. In fact, when they presented it to Coe, he famously responded that it wasn’t “the perfect country & western song” because it didn’t mention “mama, trains, trucks, prison, and gettin’ drunk.” Goodman later added a final verse—recited as spoken dialogue in Coe’s recording—that deliberately included all those clichés. The result was a tongue-in-cheek masterpiece that somehow managed to mock and honor country tradition at the same time.

Interestingly, although John Prine co-wrote the song, he declined to take a songwriter credit for royalties, reportedly telling Goodman he didn’t want to profit from what was intended as a joke. That gesture speaks volumes about Prine’s character—wry, generous, and unpretentious.

At first glance, the lyrics read like a straightforward lament: a man hurt because his lover never calls him by his name. But the repetition of the title line—“You Never Even Call Me By My Name”—becomes almost comically exaggerated. The narrator isn’t just wounded; he’s theatrically wounded. It is both heartbreak and parody. The brilliance lies in how the song gently exposes country music’s sentimental tropes while still embracing their emotional power.

When David Allan Coe recorded it, he brought an outlaw authenticity that grounded the humor in lived experience. Coe was already associated with the burgeoning outlaw movement alongside figures like Waylon Jennings and Willie Nelson, and his rough-edged delivery gave the song a kind of barroom credibility. Listeners could laugh at the clichés, but they could also recognize the truth behind them. After all, country music has always been about longing, identity, and the ache of being unseen.

The cultural impact of the song extends beyond its chart position. It became Coe’s signature tune, often closing his concerts with the crowd enthusiastically singing along to the final verse. The spoken ending—half confession, half parody—remains one of the most quoted moments in country music history. In an era when Nashville was increasingly polished, the song reminded audiences that country could still laugh at itself.

Musically, the arrangement is deceptively simple: steady acoustic rhythm, understated instrumentation, and Coe’s conversational phrasing. There are no grand production flourishes. The power lies in the storytelling. That simplicity reflects the folk roots of both Goodman and Prine, who understood that the best songs leave room for the listener’s own memories.

And perhaps that is why the song endures. Beneath the humor, there is something quietly poignant. To not be called by one’s name is to feel unseen, unacknowledged. The line carries a universal sting. We all long, at some point, to be recognized—not as a caricature, not as a stereotype, but as ourselves.

In the twilight glow of memory, “You Never Even Call Me By My Name” feels like a gentle wink from another era—a time when songs could be clever without being cynical, sentimental without being saccharine. It stands as a testament to the songwriting brilliance of Steve Goodman and John Prine, and to the interpretive power of David Allan Coe. A parody, yes—but also a love letter to country music itself.