A Promise That Outlives Time, Memory, and Farewell

As Long As I Live is not a song that announces itself with drama or spectacle. It arrives quietly, carrying the weight of decades, spoken more than sung, remembered more than performed. When Johnny Cash and Emmylou Harris recorded this duet in 1988, they were not chasing radio trends or chart positions. They were preserving something older, deeper, and far more enduring: a promise that refuses to fade with time.

Released on October 1, 1988, As Long As I Live appears on Water from the Wells of Home, the 75th studio album by Johnny Cash. The album reached No. 48 on the Billboard Top Country Albums chart, a modest position that hardly reflects its emotional gravity. The duet itself was not released as a commercial single and did not enter the major charts. Yet its absence from chart listings is part of its quiet power. This is music that belongs to memory, not competition.

The song itself was written and first recorded by Roy Acuff, one of the foundational figures of country music. Acuff introduced As Long As I Live in the late 1940s, during a period when country songs often spoke directly to separation, loss, and unbroken devotion. His original recording reached No. 1 on the Billboard Most Played Juke Box Folk Records chart, confirming how deeply its message resonated in postwar America. The lyrics offered no clever twists, no irony, no escape. Love, once given, remained. Even after parting, it endured.

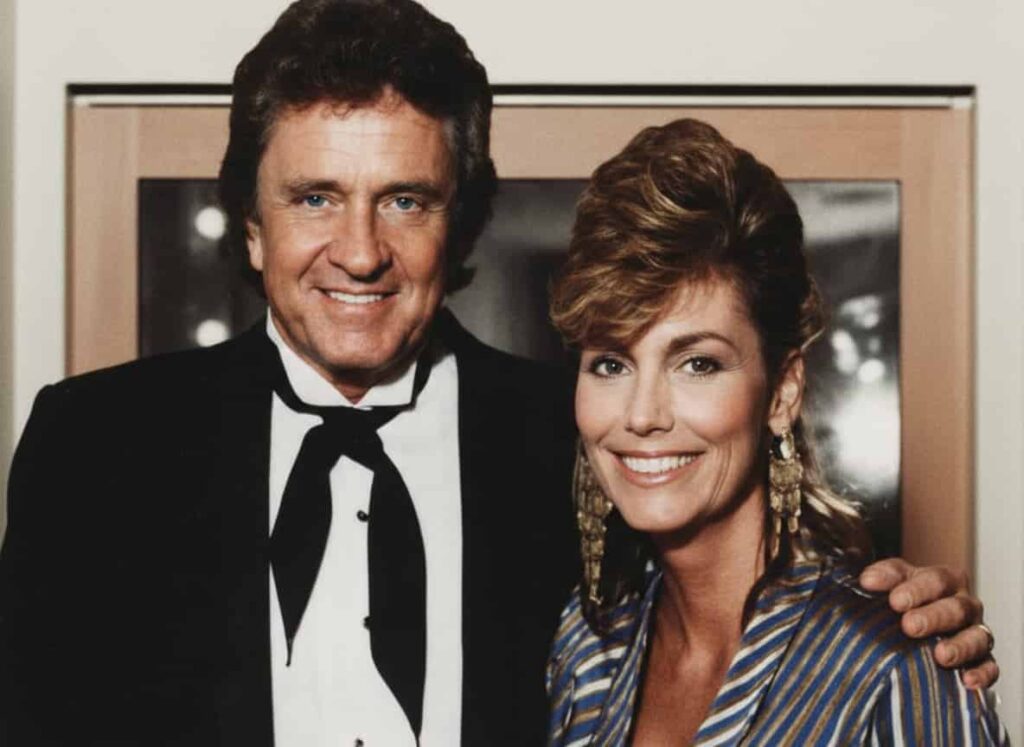

By the time Johnny Cash revisited the song more than forty years later, he carried a lifetime of such themes within his voice. His partnership with Emmylou Harris was already well established by 1988. Harris had become one of Cash’s most trusted musical companions, particularly in his late career, where tenderness and reflection replaced bravado. Their voices do not compete here. They listen to one another. Cash’s weathered baritone sounds like memory itself, while Harris answers with clarity and restraint, never overpowering, never distant.

The story behind this recording is inseparable from the album’s concept. Water from the Wells of Home was designed as a gathering of voices that mattered to Cash, artists who represented continuity rather than novelty. In that context, choosing a Roy Acuff song was deliberate. Acuff was not just a songwriter. He was a symbol of country music’s moral and emotional core. By returning to As Long As I Live, Cash was acknowledging a lineage, a debt, and a shared understanding of love as commitment rather than convenience.

Lyrically, the song is almost stark in its honesty. The narrator does not deny regret. The parting was spoken easily, forgetting promised lightly, but the truth refuses to cooperate. Memory remains. Love remains. The repeated vow, “as long as I live,” stretches time into something immeasurable. One hour or one hundred years are treated as equals. What matters is not duration, but constancy.

In the hands of Cash and Harris, the song becomes less about romance and more about endurance. It speaks to lives already lived, to promises tested by time rather than youth. There is no bitterness in their delivery. Only acceptance. Love, once true, does not require hope or reunion to justify itself. It simply exists.

This recording stands as one of the quiet triumphs of late-period Johnny Cash. It does not shout. It does not plead for relevance. It trusts the listener to recognize truth when it is spoken plainly. Emmylou Harris, with her instinct for emotional balance, ensures that the song never collapses under its own weight.

As Long As I Live endures because it refuses to decorate sorrow or soften devotion. It tells the truth slowly, patiently, and without apology. And for those who have carried memories longer than they expected, its promise feels less like a lyric and more like a reflection of life itself.