The meaning of this song is that a person would rather their loved one simply leave than have to endure a painful goodbye.

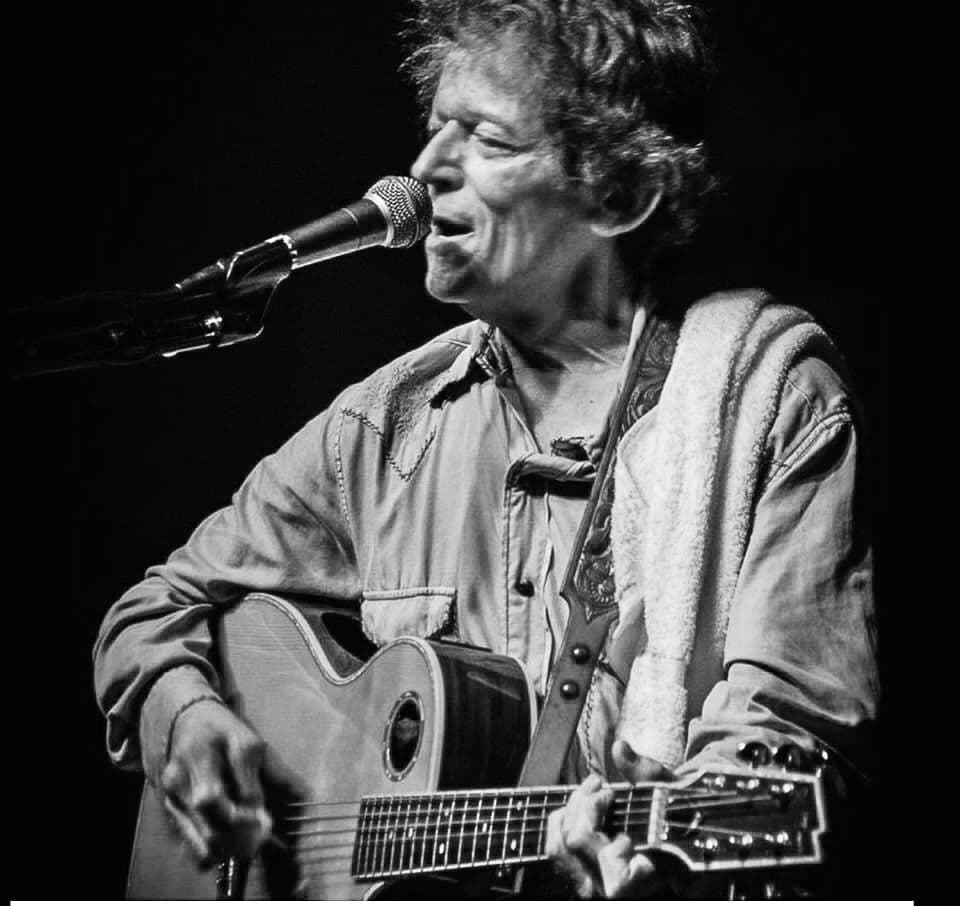

In the vast, sprawling landscape of 1970s country music, few voices resonated with the same effortless, natural ache as Johnny Rodriguez. A son of Texas with a voice as smooth as a polished river stone, he emerged from humble beginnings to become one of the genre’s biggest stars. While hits like “Ridin’ My Thumb to Mexico” and “Love Put a Song in My Heart” cemented his place in the charts, it was a deeper cut from his 1974 album “Songs About Ladies and Love” that truly captured the raw, vulnerable heart of his sound. That song was “I’m Not That Good at Goodbye”.

Penned by the legendary songwriting duo of Bob McDill and the great Don Williams, this ballad is a masterclass in emotional economy. Unlike a rambling epic, it’s a tight, focused plea delivered with a quiet, devastating finality. It’s a song that understands the sting of a farewell, the way it lingers and makes the past unbearable. The story it tells is simple yet profoundly relatable: a relationship is ending, and the narrator knows they can’t handle the conventional, drawn-out severance. They’d rather their partner just leave, a clean break without the pretense of a polite conversation. “Don’t tell me you’re leaving if you go,” the lyrics state, “Just let me turn my head while you walk out the door.” It’s a sentiment that speaks volumes about the depth of their love and the fragility of their heart.

The song’s power lies in its restraint. There are no soaring choruses or histrionic moments. Instead, Rodriguez delivers the words with a weary acceptance, his voice carrying the weight of a hundred heartbreaks. When it was released as a B-side to “I’d Just Have to Learn to Stay Away From You”, it was a quiet triumph. While the A-side was a respectable hit, “I’m Not That Good at Goodbye” found a life of its own, becoming a beloved staple for fans who understood its quiet desperation. The tune, with its gentle steel guitar and understated rhythm, feels like a warm, melancholic embrace, a soundtrack to that moment you realize some endings are just too painful to witness. It was a testament to the fact that for all the upbeat, honky-tonk anthems of the era, country music’s true genius often resided in the sad, simple truths. This song, in all its tear-stained honesty, is a prime example of that very genius.