A haunting ballad of lost youth and restless streets, where innocence fades under the shadow of the “black-eyed boys.”

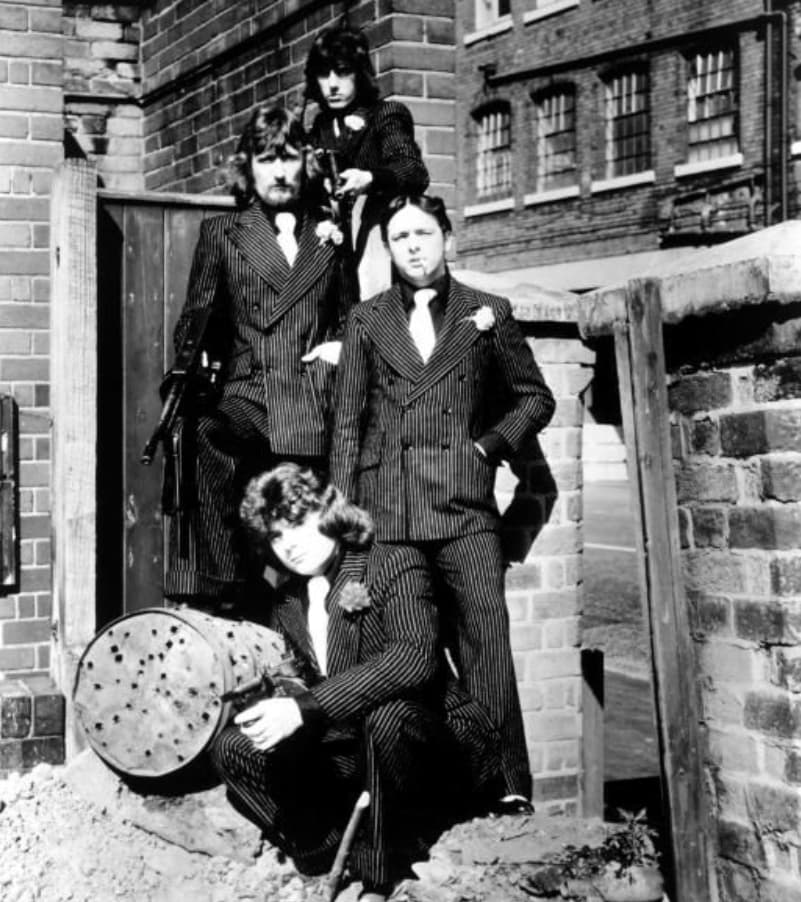

When “The Black-Eyed Boys” was released in 1974 by Paper Lace, the British pop group from Nottingham, it arrived at a time when the band was riding the extraordinary momentum of their transatlantic smash “The Night Chicago Died.” Issued as a single from the album “Paper Lace” (Mercury Records), the song did not replicate the chart-topping triumph of its predecessor, but it nonetheless secured respectable positions: it reached the Top 20 in the UK Singles Chart (peaking at No. 11) and charted modestly in the United States, reflecting the group’s brief yet intense period of international recognition. Those chart placements are important to remember, because they frame the song not as a fleeting B-side curiosity, but as a genuine follow-up during the height of the band’s commercial visibility.

Paper Lace, led by vocalist Philip Wright, were often categorized within the glam-tinged pop of the early 1970s, yet “The Black-Eyed Boys” carried a distinctly different emotional texture. Where “The Night Chicago Died” unfolded like a dramatic newspaper headline set to music, “The Black-Eyed Boys” turned inward, cloaked in an almost gothic atmosphere. The production—helmed by Mitch Murray and Peter Callander, the songwriting and production duo behind many British hits—balanced chiming guitars with an urgent rhythmic pulse. But it was the storytelling that lingered.

The song paints a vivid picture of a young girl—often interpreted as a symbol of innocence—lured by the mysterious “black-eyed boys.” These figures are never fully defined, and therein lies their power. Are they rebels? Outsiders? A metaphor for temptation itself? The ambiguity gives the song its lasting resonance. The phrase “black-eyed” suggests bruised knuckles, street fights, and restless nights. It conjures images of youths on the fringes of society, misunderstood and romanticized in equal measure. In the early 1970s, Britain was wrestling with cultural shifts, economic uncertainty, and the rise of youth subcultures. The song quietly captures that unease without preaching or moralizing.

Musically, “The Black-Eyed Boys” is structured with a driving chorus that contrasts against more restrained verses. Wright’s vocal delivery is earnest and slightly plaintive, conveying both warning and wonder. There is a sense that the narrator stands at a distance, observing the unfolding story with a mixture of concern and nostalgia. It is this emotional layering that separates the track from more disposable pop fare of the era.

Behind the scenes, Mitch Murray and Peter Callander were known for crafting songs that balanced narrative drama with commercial hooks. Their earlier successes had demonstrated a keen understanding of radio sensibilities. Yet here, they allowed a darker hue to seep through the melody. It is worth noting that in 1974, British pop was awash with glam flamboyance and American soft rock influences. Against that backdrop, “The Black-Eyed Boys” felt slightly off-center—more reflective, less celebratory.

The meaning of the song has often been debated. Some listeners hear it as a cautionary tale about young women falling under the sway of dangerous charm. Others interpret it more broadly as a lament for lost innocence, a universal story of leaving home and discovering that the world is less forgiving than imagined. There is no overt moral; instead, there is a lingering sadness. The black-eyed boys are not villains in the traditional sense—they are emblematic of a stage in life where rebellion and vulnerability intertwine.

Listening to it now, decades removed from its chart run, one can’t help but feel the texture of that era—the crackle of vinyl, the warmth of analog production, the earnest ambition of young bands hoping to carve their place in history. “The Black-Eyed Boys” may not have achieved the towering commercial heights of “The Night Chicago Died”, but it stands as one of Paper Lace’s more emotionally complex recordings.

In retrospect, the song feels like a time capsule. It reminds us that pop music in the 1970s was not merely about glitter and spectacle; it was also about storytelling, about capturing fleeting moments of change. “The Black-Eyed Boys” endures not because it dominated charts worldwide, but because it whispers rather than shouts. It leaves space for memory—for the quiet recognition of roads taken, of youthful faces glimpsed under streetlights, and of the bittersweet understanding that some chapters close before we fully comprehend them.