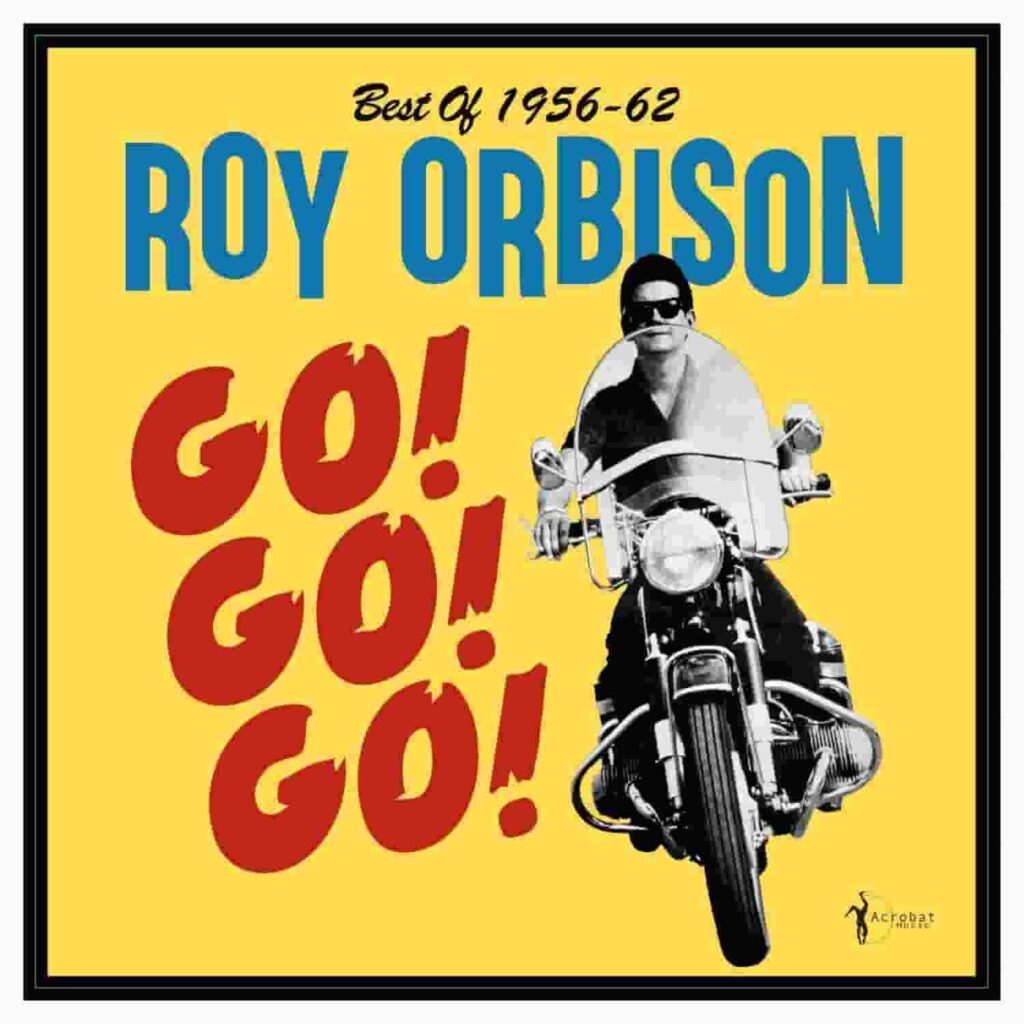

A restless burst of youth and motion, capturing Roy Orbison before the sorrow, before the shadows, when rock and roll still ran on pure momentum and hunger.

When Roy Orbison released “Go Go Go” in 1956, the world had not yet met the solemn, operatic balladeer who would later define heartbreak with songs like “Only the Lonely” or “Crying.” This was an earlier Roy Orbison, lean and impatient, shaped by the raw electricity of Sun Records and the kinetic spirit of mid-1950s rockabilly. “Go Go Go” appeared as the B-side to “Ooby Dooby,” his first national hit, issued by Sun Records as Sun 242. While “Go Go Go” did not chart independently on the Billboard Hot 100, it traveled alongside a single that reached No. 59 in the United States, introducing Orbison’s name to a wider audience for the first time.

These facts matter because they place “Go Go Go” at a crucial crossroads. It belongs to the brief but vital Sun period of Roy Orbison, when he was still experimenting with identity, speed, and attitude. The song was recorded in Memphis with the stripped-down production Sun Records was famous for. No orchestration, no dramatic pauses, no operatic crescendos. Just rhythm, bite, and forward motion. It is rock and roll before refinement, before introspection, before tragedy entered the voice.

Lyrically, “Go Go Go” is built on movement and rejection. The narrator is done waiting, done explaining, done slowing down. “Can’t be square, can’t be slow” is not just a rhyme, it is a worldview. In the language of 1950s youth culture, to move was to live. To hesitate was to be left behind. The song’s repeated insistence on motion reflects the postwar American hunger for freedom, speed, and reinvention. Cars, jukeboxes, neon streets, and the promise of somewhere better just down the line are all implied, even when not explicitly named.

What makes “Go Go Go” especially compelling in hindsight is how completely it contrasts with the Roy Orbison the world would soon come to know. This is not the voice of vulnerability. This is the voice of bravado. The singer is confident, restless, almost defiant. There is no emotional surrender here, no wounded pride. Instead, there is swagger and a belief that something better waits ahead, if only one keeps moving.

Historically, the song also reflects the influence of Elvis Presley, Carl Perkins, and the broader Sun Records sound. Orbison admired Elvis deeply, and in “Go Go Go,” that influence is unmistakable. The phrasing, the rhythmic push, and the slang all place the song firmly within the rockabilly tradition. Yet even here, one can hear hints of Orbison’s unique sensibility. His voice, already smoother and more controlled than many of his peers, rises above the simple structure, suggesting a singer capable of far more emotional range than this early material required.

The meaning of “Go Go Go” ultimately lies in its urgency. It is a song about refusing to settle, about choosing momentum over comfort. It celebrates the idea that life is something to chase, not wait for. In that sense, it captures a moment in cultural history when rock and roll was less about reflection and more about escape. The future was not something to fear. It was something to race toward.

For listeners familiar only with Orbison’s later masterpieces, “Go Go Go” can feel almost surprising. Yet it is precisely this contrast that gives the song its lasting value. It documents the beginning of a journey, a young artist still running forward, unaware of the emotional depths he would later plumb. In the broader story of Roy Orbison, “Go Go Go” stands as a reminder that every great voice begins with motion, hunger, and the simple need to move.