Love the One You’re With — a simple truth about love, sung at a moment when the world was coming apart

When “Love the One You’re With” first reached the airwaves in 1970, it arrived not as a grand manifesto, but as a calm, almost conversational reminder — a song that suggested emotional honesty in a time of confusion, idealism, and quiet disillusionment. Written and performed by Stephen Stills, it was released as the lead single from his self-titled debut solo album, Stephen Stills, and it quickly found its place in the musical and cultural fabric of the era.

Commercially, the song performed strongly. Upon its release in mid-1970, “Love the One You’re With” climbed to No. 14 on the Billboard Hot 100, making it Stephen Stills’ most successful solo single. The album Stephen Stills fared even better, reaching No. 3 on the Billboard 200, a testament to both his reputation and the appetite for thoughtful, roots-based songwriting at the dawn of a new decade. These numbers mattered at the time — but the song’s real legacy lies elsewhere, in its emotional clarity and enduring relevance.

The story behind the song is often misunderstood. On the surface, the title sounds almost flippant, as if it were advocating emotional convenience or romantic compromise. But Stephen Stills was never that careless a writer. The line “If you can’t be with the one you love, love the one you’re with” was not meant as an instruction to forget or betray deep feelings. Instead, it reflects a moment of acceptance — the recognition that life does not always give us what we want, when we want it, and that there is dignity in being present rather than endlessly yearning.

Stills wrote the song during a period of transition. Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young were fractured by internal tensions, and the optimism of the late 1960s was giving way to fatigue. The Vietnam War dragged on, social movements splintered, and personal relationships — even among musicians who had shared stages and ideals — grew complicated. In that climate, “Love the One You’re With” feels less like a love song and more like a philosophy: a call to ground oneself in the here and now.

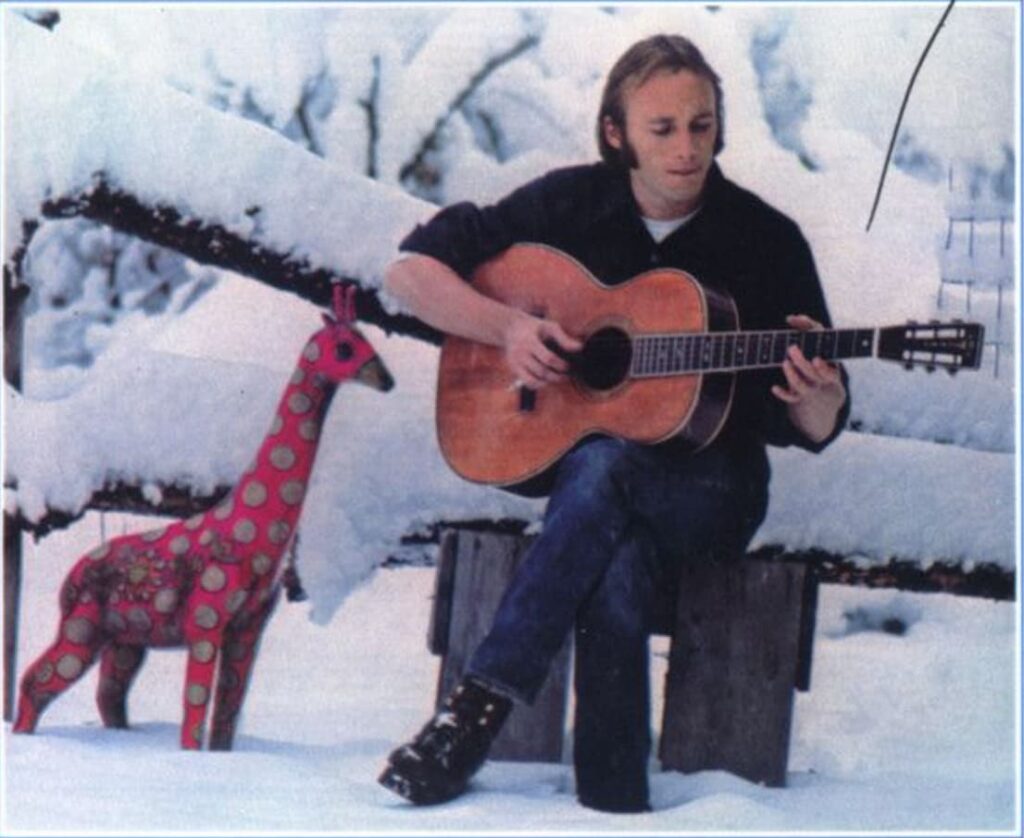

Musically, the track is deceptively simple. Built around an acoustic guitar riff and warm harmonies, it carries the unmistakable DNA of the Laurel Canyon sound — relaxed, sun-drenched, and intimate. The gospel-tinged backing vocals, provided by friends from the California music community, give the song a communal feel, as if it were meant to be sung not just to an audience, but among them. There is comfort in that sound, the comfort of shared understanding.

What makes the song especially resonant for listeners who have lived through decades of change is its emotional restraint. Stills does not plead. He does not dramatize. His voice is steady, reflective, almost weary — the voice of someone who has already asked the big questions and is learning to live with the answers. In that sense, “Love the One You’re With” feels like advice passed quietly from one life stage to another, not shouted, not insisted upon.

Over the years, the song has been covered, quoted, and sometimes misunderstood, yet it has never truly aged. Because its message is not tied to fashion or politics — it is tied to human limitation. We all know what it means to want what is absent, to carry unresolved feelings, to look backward while life insists on moving forward. This song does not judge that impulse; it gently redirects it.

In Stephen Stills’ long and influential career, “Love the One You’re With” stands as a moment of personal clarity. It captures a man stepping out from the collective voice of a supergroup and speaking plainly, in his own name, about the quiet compromises of the heart. Not surrender — but acceptance.

And perhaps that is why the song still lingers. It reminds us that love is not always about destiny fulfilled. Sometimes it is about presence. About choosing warmth over distance. About finding meaning not in what might have been, but in who is standing beside us now.