A Fierce Anthem of Human Unity and Moral Reckoning in a Fractured Age

When “Family of Man” by Three Dog Night was released in 1972, it did more than climb the charts—it carried the urgency of its time, echoing across a world weary of division yet still yearning for connection. The song reached No. 12 on the Billboard Hot 100 in the United States in early 1972, becoming one of the band’s significant Top 20 hits during their remarkable run of radio dominance. It was featured on the album Seven Separate Fools (1972), a record that continued the group’s streak of gold-selling success and reinforced their reputation as one of the most reliable hitmakers of the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Written by Paul Williams and Roger Nichols, the same songwriting duo behind “An Old Fashioned Love Song” (also a major hit for Three Dog Night), “Family of Man” is in many ways a spiritual cousin to that earlier composition—but sharper, more urgent, less romantic and more admonishing. Where “An Old Fashioned Love Song” wrapped its message in warmth and melody, “Family of Man” arrives like a warning bell, ringing with moral insistence.

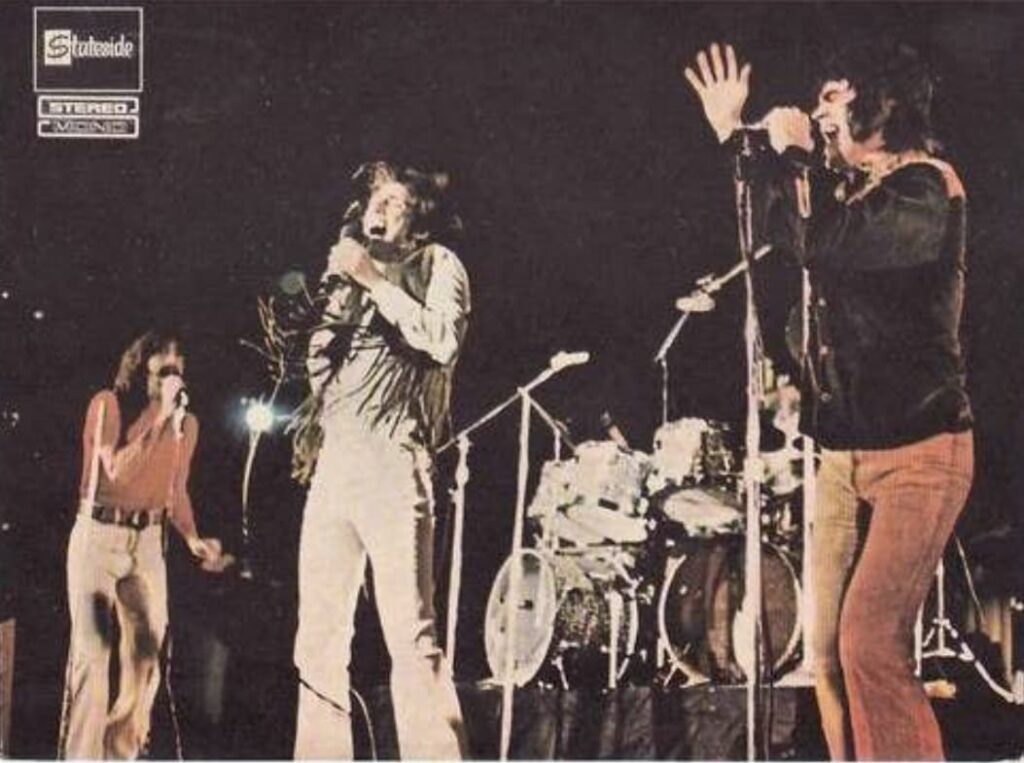

Musically, the track showcases the signature strength of Three Dog Night—the power of three distinct lead vocalists: Chuck Negron, Cory Wells, and Danny Hutton. On this track, Cory Wells takes the commanding lead, delivering the lyrics with a conviction that borders on prophetic. His voice cuts through the arrangement—firm, clear, slightly roughened by emotion—supported by the band’s tight instrumentation and soaring harmonies. The production is bold but not overindulgent; it serves the message.

And what a message it is.

“Family of Man” confronts humanity with itself. At its core, the song is a plea—and perhaps a reprimand—directed at a divided world. The early 1970s were marked by the lingering shadows of the Vietnam War, civil rights struggles, generational conflict, and political distrust. Rather than taking a partisan stance, the song speaks in universal terms. It reminds listeners that beyond ideology, beyond borders, beyond pride, we belong to the same human family.

The repeated refrain—“We’re a family of man”—feels almost biblical in tone, yet grounded in contemporary reality. There is both hope and disappointment woven into its lines. The song does not naively assume unity exists; it insists that it must be remembered.

What makes “Family of Man” endure is not merely its chart performance, but its emotional gravity. Three Dog Night had already established themselves as interpreters of outside songwriters—rarely composing their own material, yet possessing a rare instinct for choosing songs that spoke to the cultural moment. They transformed compositions by others into definitive recordings. In that sense, their artistry lay not only in performance but in discernment.

By 1972, the band was already a powerhouse, with a string of hits including “Joy to the World,” “Mama Told Me (Not to Come),” “One,” and “Black and White.” “Family of Man” fit seamlessly into this lineage, yet it carries a slightly more mature, reflective tone. It feels less like celebration and more like reckoning.

Listening to it today, one cannot help but feel a quiet ache of recognition. The world has changed, yet the song’s central truth remains uncomfortably relevant. That is the paradox of timeless music: it reminds us that progress and struggle often walk hand in hand.

The arrangement itself builds with restrained intensity—piano-driven verses leading into expansive choruses. There is no excess here, no flamboyant solo designed to distract. The focus remains on the lyric. The harmonies—always a hallmark of Three Dog Night—serve as a symbolic embodiment of the song’s theme: distinct voices blending into one cohesive whole. In that sense, the band becomes a living metaphor for the “family” they sing about.

Over half a century later, “Family of Man” stands as more than a Top 20 single. It stands as a testament to an era when pop music dared to ask moral questions without surrendering melody. It carries the spirit of a generation wrestling with its conscience, yet unwilling to abandon hope.

And perhaps that is why it lingers—not simply in playlists, but in memory.