A Haunting Self-Elegy on the Reckoning of a Dissolute Past

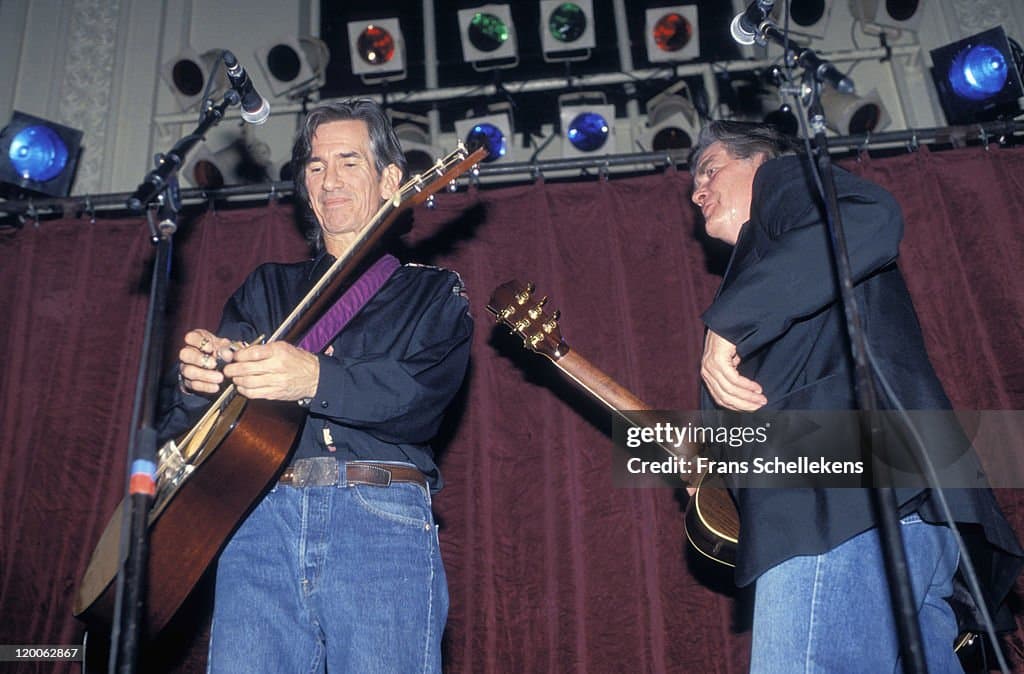

It’s a strange thing, isn’t it, how a song can feel like holding a long-lost photograph, the edges softened by time and regret? When we speak of Townes Van Zandt—and in the context of this searing song, the posthumously released live collaboration with his great contemporary, Guy Clark, found on the 2020 album FolkScene, Los Angeles—we’re talking about the poetry of the dark night of the soul. The song in question is “Rake,” and it stands as a testament, a stark confession lifted from his 1971 album, Delta Momma Blues. As was often the case for an artist of Townes Van Zandt‘s caliber, whose impact was a slow burn among his peers and devoted listeners rather than a sudden explosion onto the airwaves, “Rake” did not achieve a chart position in the conventional sense upon its original release. It’s a truth that only adds to the song’s mystique; its power exists outside the fickle confines of popular commercial success, resonating deeply in the quiet corners of the heart where one grapples with mortality and wasted years.

The genesis of “Rake” is deeply entwined with the legend of Townes Van Zandt himself—the brilliant, nomadic Texas troubadour who wrestled with addiction, mental illness, and a profound, almost spiritual melancholy. The word ‘rake’ itself is an archaic term for a dissolute man, a womanizer, a hell-raiser, and the song is a chilling self-portrait of a life spent in reckless pursuit of ephemeral pleasure. It’s a narrative of an aging libertine, reflecting on his youth spent running with the moon, “covering my lovers with flowers and wounds,” and thinking his “laughter the devil would frighten.” The story, therefore, is autobiographical in spirit, embodying the lifestyle of excess and the eventual physical and spiritual ruin that haunted Townes Van Zandt‘s life. He channeled his own pain and self-destruction into something timeless and terrifying.

The meaning of “Rake” is a profound meditation on the inescapable reckoning for a life of wanton living. The early verses capture a dazzling, defiant arrogance—the rake is the sea, and time is merely the water passing through him. But the pivot arrives when he speaks in the present, seeing the judgment in the eyes of his listeners: “You look at me now, and don’t think I don’t know / What all your eyes are a sayin’.” The former lover of women can “hardly stand” and is “bent and he’s broken,” his body a mere wreckage. The ultimate, crushing blow is delivered when his own “laughter turned ’round, eyes blazing and / Said ‘my friend, we’re holdin’ a wedding’.” This is the chilling climax—the marriage of the rake’s wild “night” to the inevitable “day” of judgment, a cruel punishment for his pride. His one hope, the thought that he’d “be forgiven,” is cruelly dashed by his past actions personified. The final lines, where the dark air is like “fire on my skin” and the moonlight is “blinding,” speak to the utter loss of the comfort he once found in the night. It’s a parable of the Prodigal Son without redemption, a bleak, unflinching look at the cost of trading one’s future for momentary freedom. This is what makes Townes Van Zandt‘s work endure; it is utterly real, devoid of comfort, but rich with the tragic beauty of human failure.