A Voice Dressed in Black, Speaking for the Forgotten and the Left Behind

When Johnny Cash released “Man in Black” in 1971, it arrived not merely as a song, but as a declaration—plainspoken, unadorned, and resolutely moral. Issued as the title track of the album Man in Black, the song was written and recorded by Cash himself at a moment when America was deeply fractured by war, inequality, and social unrest. Upon its release as a single in early 1971, “Man in Black” reached No. 3 on the Billboard Hot Country Singles chart, confirming that its message resonated widely, even as it challenged listeners to look more closely at the world around them.

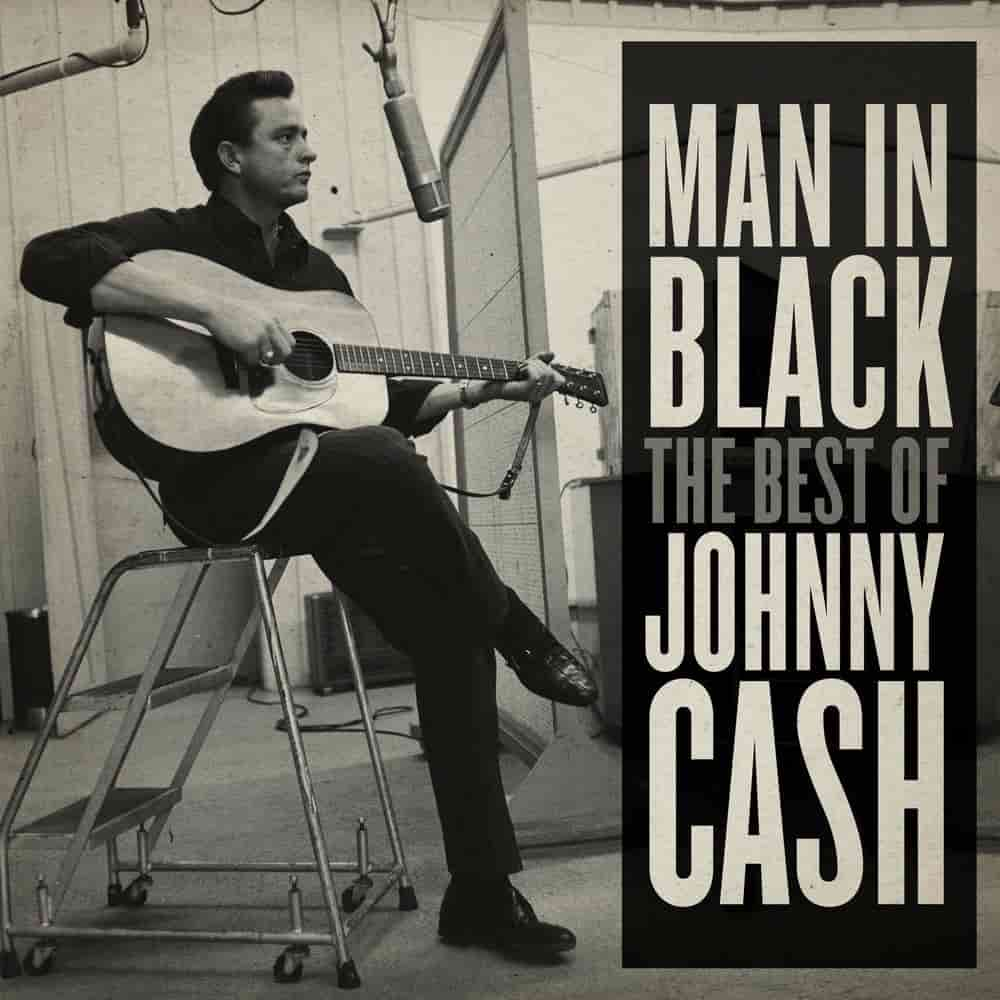

By then, Johnny Cash was already an institution. He had crossed over from country to pop, gospel, folk, and protest music, carrying his unmistakable baritone with him. But “Man in Black” did something different. Rather than telling a story through a character or narrative, Cash stepped forward as himself. The song is structured as a calm explanation—almost conversational—of why he appears on stage dressed head to toe in black. Yet beneath that simplicity lies a pointed critique of American society.

Cash had been wearing black regularly since the late 1960s, but the song served as a public reckoning. Line by line, he explains that black is worn not for fashion, not for mourning in a conventional sense, but as a symbol of solidarity. He sings for “the poor and the beaten down,” for those “living in the hopeless, hungry side of town,” and for prisoners who have long paid for crimes while society conveniently forgets them. In Cash’s vision, black becomes a uniform of conscience.

The timing matters. America in 1971 was weary—Vietnam dragged on, trust in politicians was eroding, and economic disparities were increasingly visible. Unlike many protest songs of the era that relied on anger or poetic abstraction, “Man in Black” is restrained and direct. Cash does not shout. He does not accuse by name. Instead, he offers a moral inventory, calmly reminding listeners that prosperity has not reached everyone, and that responsibility does not end at personal comfort.

Musically, the song is deceptively modest. The arrangement is sparse, anchored by acoustic guitar, subtle rhythm, and Cash’s steady vocal delivery. There are no dramatic flourishes to distract from the words. This restraint amplifies the song’s authority. Cash sounds less like a performer and more like a witness—someone who has seen enough of life to speak without embellishment.

The album Man in Black reinforced this image. It followed At San Quentin (1969) and At Folsom Prison (1968), records that had already cemented Cash’s connection to the incarcerated and marginalized. The title track acted as a thesis statement for that phase of his career: fame had not insulated him from empathy. If anything, it had sharpened his sense of obligation.

Importantly, “Man in Black” does not present Cash as a savior. In one of its most striking lines, he admits that someday, when society has mended its ways, he might wear brighter colors. It is a humble acknowledgment that the problem is collective—and unresolved. That conditional hope gives the song its lingering power. The black clothing is not permanent; injustice, in Cash’s view, should not be either.

Over time, the song has become inseparable from Johnny Cash’s identity. The nickname “The Man in Black” endured for the rest of his life, shorthand for an artist who stood apart from trends while remaining deeply engaged with the moral questions of his era. Today, “Man in Black” endures not because it belongs to a political moment, but because it speaks to a timeless unease—the gap between what a society celebrates and whom it leaves behind.

In the end, the song asks very little of the listener. It does not demand allegiance, only awareness. And perhaps that is why it still carries weight decades later: it reminds us that sometimes the strongest statement is made quietly, by simply choosing what one stands for—and wearing it without apology.