When Genius Meets Its Reckoning: The Price of Fame and the Fall of Jerry Lee Lewis

In the late months of 1957, Jerry Lee Lewis stood at the very summit of American popular music. At just twenty two, he was not merely successful. He was seismic. His records dominated jukeboxes, his name sat high on the charts, and his explosive piano style redefined what rock and roll could look like and sound like. With “Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin’ On” reaching No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100 and “Great Balls of Fire” climbing to No. 2, Lewis appeared destined for a career without limits. Yet history would remember him not only for his music, but for the moment when fame exposed a darker truth and the stage lights suddenly went out.

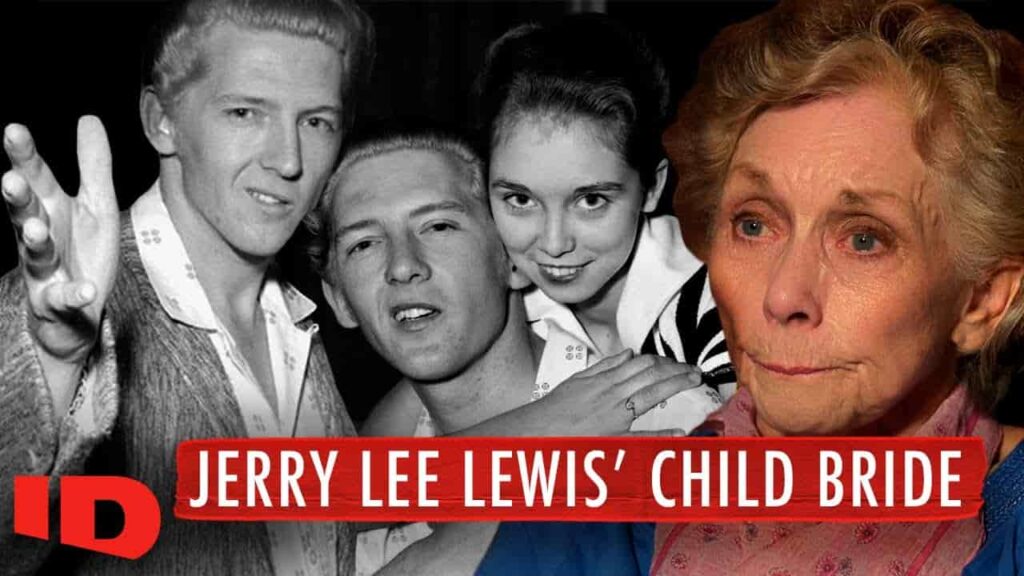

The collapse came swiftly and publicly. During a 1958 tour of the United Kingdom, journalists uncovered that Lewis had married Myra Gale Brown, his thirteen year old cousin, while still legally married to another woman. The revelation detonated his career almost overnight. Concerts were canceled, radio stations pulled his records, and a performer once paid thousands per night found himself reduced to a handful of pounds per show. In the rigid moral climate of the late 1950s, the scandal was unforgivable, and the punishment absolute.

From a musical standpoint, the timing could not have been more catastrophic. Jerry Lee Lewis was not an emerging artist. He was already one of the defining architects of early rock and roll, standing shoulder to shoulder with Elvis Presley, Little Richard, and Chuck Berry. His recordings for Sun Records, particularly under producer Sam Phillips, fused country, gospel, and rhythm and blues into something feral and electric. His debut album, “Jerry Lee Lewis” released in 1958, should have cemented his place as a long term cultural force. Instead, it became a marker of what might have been.

The deeper tragedy, however, extends beyond charts and lost acclaim. The public conversation of the time focused almost exclusively on the destruction of a prodigy. Headlines mourned the fall of a genius, the waste of talent, the loss to popular music. What remained largely unspoken was the experience of Myra Gale Brown herself. She did not step into a glamorous love story. She was pulled into a world shaped by power imbalance, secrecy, and fear.

In later years, Myra’s own accounts revealed a life marked by control, intimidation, and violence. Her story reframed the scandal entirely. What had been treated as a salacious footnote in rock history emerged as a case study in how society excuses celebrated men while silencing those without power. The myth of the untouchable male genius allowed abuse to be minimized, rationalized, or ignored altogether.

Listening now to the early recordings of Jerry Lee Lewis, the contradiction is impossible to escape. The same hands that hammered joy and rebellion into the piano keys also belonged to a man capable of profound moral failure. Songs like “Great Balls of Fire” still burn with reckless vitality, but they now carry an added weight, a reminder that brilliance does not absolve cruelty.

The meaning of this story, with the distance of time, has shifted. It is no longer simply about scandal or canceled careers. It stands as a warning about the dangers of idol worship, about what happens when success shields behavior from scrutiny. The price of fame, in this case, was not only paid by the artist. It was paid by a child whose voice was unheard while the world argued about records and reputations.

Today, the collapse of Jerry Lee Lewis remains one of the most sobering chapters in music history. It forces a reckoning that goes beyond nostalgia. It asks whether talent should ever outweigh accountability, and whether admiration can blind even thoughtful societies to human suffering. In that sense, the story endures not as gossip from a bygone era, but as a moral echo that still resonates whenever art and power collide.