The Hardest Road: An Ode to Despair, Desperation, and the Final, Fatal Embrace

A haunting chronicle of a life defined by abandonment, addiction, and the grim acceptance of a predetermined, tragic end.

For those of us who came of age when the promise of the American dream began to fray, when the shine wore off the 1960s’ idealism and gave way to a bleaker, more sober reality, there are songs that feel less like entertainment and more like shared history—a whispered confession in the lonely hours. Townes Van Zandt‘s “Waiting Around To Die” is one of those seminal works. It wasn’t a commercial hit destined for a fleeting top 40 spot; indeed, Townes Van Zandt was a songwriter’s songwriter, a cult figure whose brilliance rarely translated into mainstream chart success, making its omission from Billboard’s Hot 100 or Country charts entirely predictable yet profoundly irrelevant to its impact. When it was first released on his 1968 debut album, For the Sake of the Song, its raw, unflinching narrative stood apart, a chilling ballad of a broken life told with devastating economy.

The song holds a special, agonizing place in the Townes Van Zandt canon, primarily because he considered it his first “serious song,” a pivotal moment where his craft moved from mere composition to gut-wrenching poetry. His first wife, Fran Petters, recalled in the documentary Be Here to Love Me that he wrote the harrowing tune while holed up for hours in the walk-in closet of their Houston home, a tiny, self-imposed studio. For a newlywed hoping for a light-hearted melody or a tender love song, Fran was met instead with this bleak masterpiece, a dark foreshadowing that seemed to hold a mirror up to the songwriter’s own troubled path.

The true meaning of “Waiting Around To Die” lies in its brutal, episodic narrative. It’s a fictional autobiography of a character born under a bad sign, moving through a life of neglect and desperation. We follow him from a childhood trauma—a father who beats his mother, who then abandons them for Tennessee—into a cycle of alcohol, gambling, and aimless rambling. He is betrayed by a woman in a “Tuscaloosa bar,” he falls into crime with a friend, is caught, and serves “two long years… waitin’ around to die” in a Muskogee prison. The final, heartbreaking stanza delivers the ultimate surrender: the narrator finds a new, loyal friend, one who “don’t drink or steal or cheat or lie”—that friend is Codeine. The protagonist, having exhausted all routes of resistance, accepts his fate, seeking solace in a substance that will make the inevitable, final wait easier. The refrain, “Well it’s easier than just a-waitin’ around to die,” is a constant, grinding acknowledgment of a cosmic futility, a man’s attempt to exert control over his own decay.

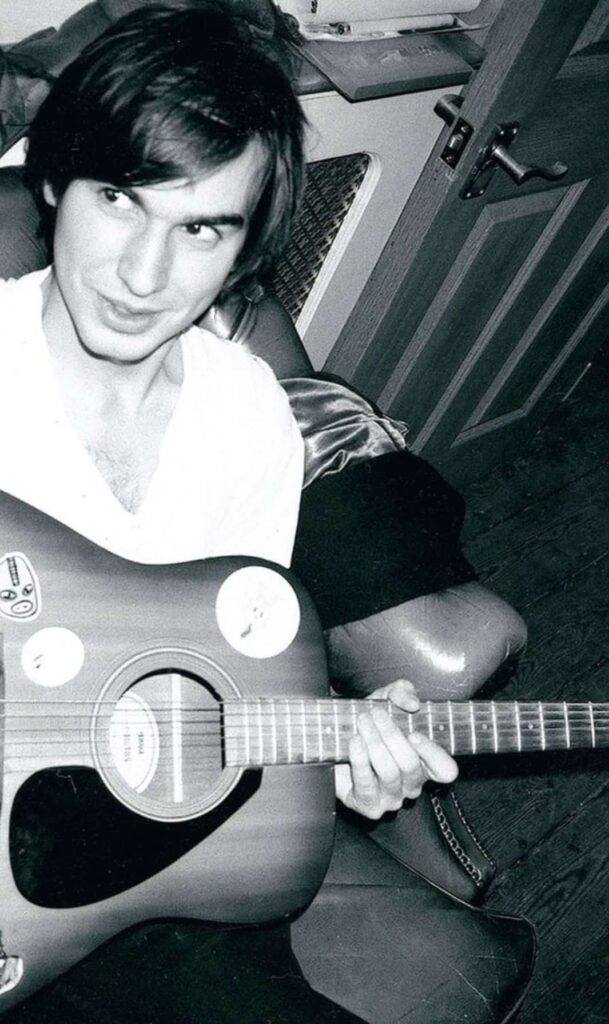

This weary, three-finger style acoustic ballad, later immortalized in the 1981 documentary Heartworn Highways—which chronicled the emerging Outlaw Country movement with artists like Guy Clark and Steve Earle—resonated with an authenticity that was palpable. The performance in the film, where a young Van Zandt sings the song for the elderly, deeply religious Uncle Seymour Washington in a small shack, remains one of the most poignant moments in music documentary history. Uncle Seymour‘s tearful reaction is a testament to the song’s universal power to move even the most hardened listener.

For older readers, who may have watched friends or family struggle against the tides of addiction and despair, the song evokes a raw, nostalgic ache. It’s the sound of a bygone era of country-folk music—stripped-down, poetic, and utterly devoid of Nashville polish. It captured a truth about the lonely American road, a world of dive bars, freight trains, and penitentiaries that existed just beyond the neon lights of commercial success. Van Zandt, who himself wrestled with bipolar disorder and profound substance abuse throughout his life until his death at the tragically young age of 52, poured his very soul into the verses. The song became a haunting, self-fulfilling prophecy, a tragic poem set to a melancholic tune, forever solidifying Townes Van Zandt as one of the most honest and gifted chroniclers of the human condition. It is not an uplifting song, but it is a necessary one, a reminder that true beauty can often be found in the deepest shadows.