More Than a Hat and Boots: A Satirical Look at the ‘Urban Cowboy’ Faux-Westerner

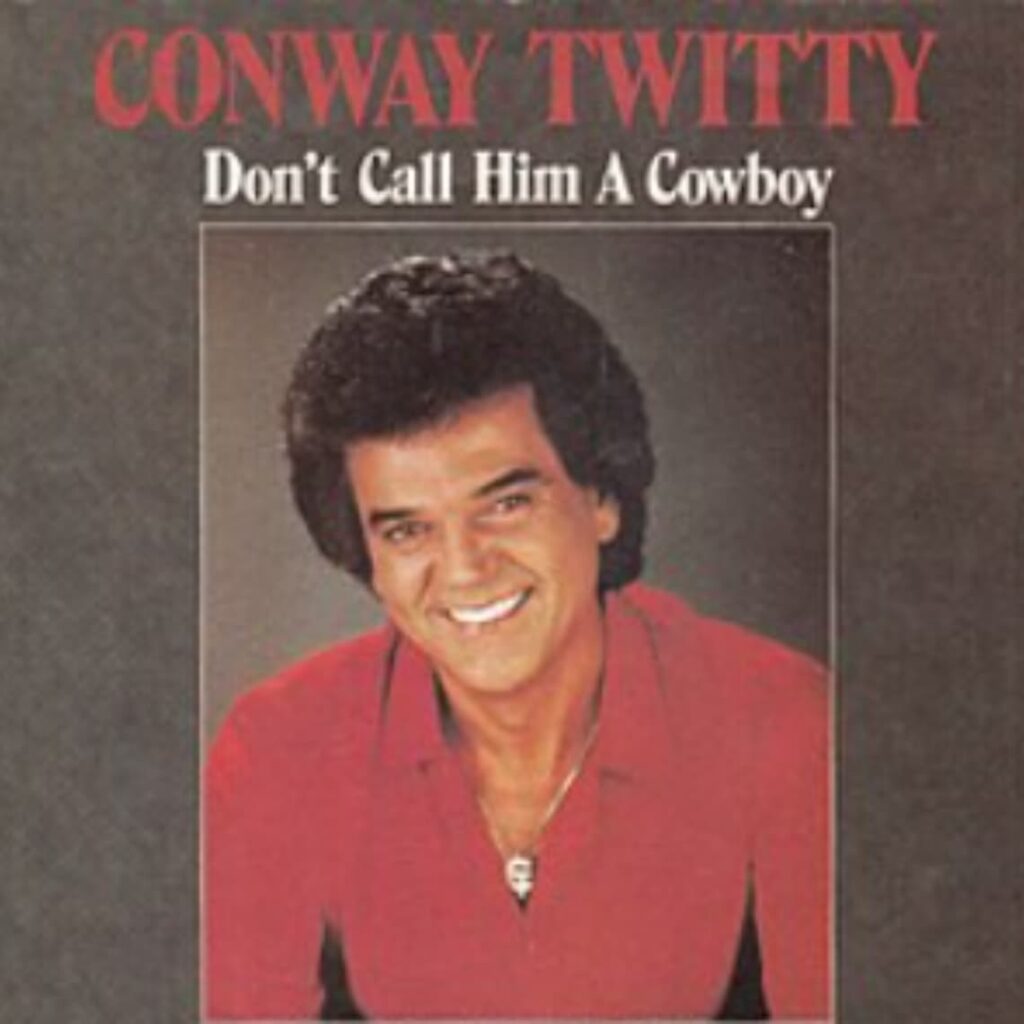

There are certain songs that, years later, instantly transport you back to a specific time and feeling, and for many, Conway Twitty‘s 1985 smash, “Don’t Call Him A Cowboy,” is one of them. Released in February 1985 as the title track and first single from the album Don’t Call Him a Cowboy, this track was a massive success, crowning the charts as Twitty’s 34th Billboard number one single on the country chart, and his astonishing 50th overall. The track also achieved the coveted number one spot in Canada, affirming its widespread appeal and his undeniable status as a country music powerhouse even into the mid-eighties. The song, penned by a talented trio—Debbie Hupp, Johnny MacRae, and Bob Morrison—was both timely and timeless, offering a witty critique that resonated deeply with the traditional country audience.

The early 1980s saw the pervasive cultural impact of the “Urban Cowboy” phenomenon, sparked by the 1980 film of the same name. Suddenly, cowboy hats, fancy boots, and pearl-snap shirts became weekend attire for city folks and suburbanites who’d never been within spitting distance of a saddle or a cattle drive. It was a time of poseurs, of the aesthetic replacing the authenticity. “Don’t Call Him A Cowboy” is, at its heart, a brilliant piece of satire directed squarely at this type of drugstore cowboy—the man who has the look down pat but none of the grit, skill, or spirit of a true working ranch hand.

The meaning is laid bare in the sharply observed lyrics, which paint a picture of a man dressed in “French designer blue jeans” and a “custom tailored vest,” whose “toughest ride he’s ever had / Was in his foreign car.” The central, double-edged caution of the song is unforgettable: “So don’t call him a cowboy / Until you’ve seen him ride.” On one level, it’s a call for substance over style, asserting that true character is revealed through action, not simply through expensive, fashionable gear. But the subtle, masterful twist—the element that gave Twitty his famous reputation for suggestive songs—is the clear innuendo. “And if he ain’t good in the saddle, Lord, you won’t be satisfied,” he croons, letting the listener know that the “ride” being referenced is far less about a horse and much more about romantic satisfaction. It’s the ultimate, wink-and-a-nod Conway Twitty delivery, taking a cultural commentary and infusing it with his signature sexy charm.

For those of us who grew up listening to the genuine article, this song offered a delightful validation of old-school country values. It was a comforting, familiar voice cutting through the manufactured shine of the pop-country crossover, reminding us that genuine cowboys earned their stripes through hard work, not department store purchases. Listening back now, the song is a beautifully preserved time capsule of the era, showcasing Conway Twitty‘s uncanny ability to adapt to changing trends while staying fundamentally true to the soulful country sound he had perfected over decades. It’s a nostalgic reminder of a simpler time when a hit song could be simultaneously number one on the charts, a cultural joke, and a romantic suggestion all rolled into one classic tune.