A quiet, sorrowful journey through heartache — “Blues Run the Game” by Jackson C. Frank

The haunting melody of “Blues Run the Game” opens Jackson C. Frank’s sole album with a weight of both resignation and restless longing. Recorded in July 1965 in London, this song was released as the lead track on his self-titled debut. Though the album sold poorly at the time and failed to chart, “Blues Run the Game” has grown in stature over the decades to become a folk standard.

At its core, “Blues Run the Game” is a meditation on inevitability. Frank opens with the lines, “Catch a boat to England, baby / Maybe to Spain / Wherever I have gone … the blues are all the same.” He suggests that running away—to another country, another life—offers no real escape: sorrow and longing follow you easily, like a shadow you can never quite outrun.

There’s a deep, melancholic wisdom in that simple truth. The “game” in the song’s title isn’t playful—it’s a cruel, unrelenting force. The blues don’t just visit; they run the game. In Frank’s world, pain is not incidental. It’s the very rhythm of life.

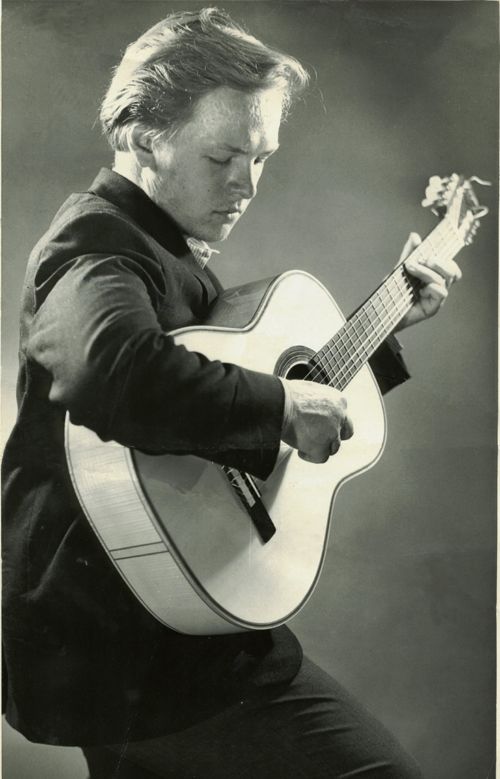

The arrangement is stark and intimate: Frank’s high tenor voice, delicate acoustic guitar, and a gently loping chord structure that feels almost conversational. He recorded the entire album in a few hours—reportedly in under three—with producer Paul Simon. During the session, he was so shy that he asked for screens so others couldn’t watch him play. That vulnerability bleeds through in his performance. The minimalism only heightens the emotional impact: there is nowhere to hide from the truth in his voice.

Behind the song lies a life scarred by tragedy. When Jackson was just eleven years old, a devastating fire at his school left him severely burned and claimed the lives of many of his classmates. That trauma cast a long shadow over his entire existence. After recovering, he leaned into music: a teacher gave him a guitar during his convalescence, and he taught himself to play, laying the foundation for his songwriting.

When he came into a substantial insurance payout at age 21, he left America for London—the very journey he sings about in “Blues Run the Game.” In London, he entered a vibrant folk scene, collaborating with the likes of Paul Simon, Art Garfunkel, and Al Stewart. But despite the promise, his life was haunted by psychological struggles. According to many accounts, he later developed serious mental-health issues, including schizophrenia, and endured long periods of homelessness.

The tragic arc of his life only deepens the meaning of “Blues Run the Game.” The loneliness he describes in the song reflects his own inner turmoil. The bitterness of his reality—his fading hopes, his perpetual sense of being an outsider—seems to have followed Frank through his declining years, shaping a song that is as intimate as it is universal.

Over the years, the song has been covered by a remarkable array of artists: Simon & Garfunkel, Nick Drake, John Mayer, Laura Marling, Counting Crows, Bert Jansch, and many more. Its enduring appeal lies in the universal truth at its heart: no matter where you run, some sadness cannot be shaken.

In film and television, “Blues Run the Game” continues to surface in poignant moments—its melancholic tone lending weight to scenes of memory, regret, and longing.

For an older listener, this song can feel like a lonely letter folded in the pocket of a well-worn coat. The imagery of travel, escape, and persistent sorrow speaks to anyone who has carried unspoken burdens for decades. Frank’s voice—soft, wounded, full of fragile hope—becomes a companion to our own memories of lost chances, of places we left, and the unquiet longing we carried home.

Though Jackson C. Frank recorded only one album, this song alone is enough to declare him a poetic soul grappling with a brutal world. “Blues Run the Game” is not merely a folk tune—it is a quiet confession, a lament, and ultimately a testament to the human spirit’s haunting resilience in the face of pain.