If I Should Fall From Grace With God — a fierce, poetic cry of exile, faith, and defiance from the Irish soul

When The Pogues released “If I Should Fall From Grace With God” in 1988, it felt less like a song and more like a declaration — loud, unruly, and brimming with history. It was the title track of their third studio album, If I Should Fall from Grace with God, an album that would become a defining statement not only for the band, but for Irish folk-punk as a whole. Upon its release, the album reached No. 3 on the UK Albums Chart, marking the commercial and artistic peak of The Pogues’ career. The song itself was not issued as a charting single, yet its impact has endured far beyond any position on a singles list.

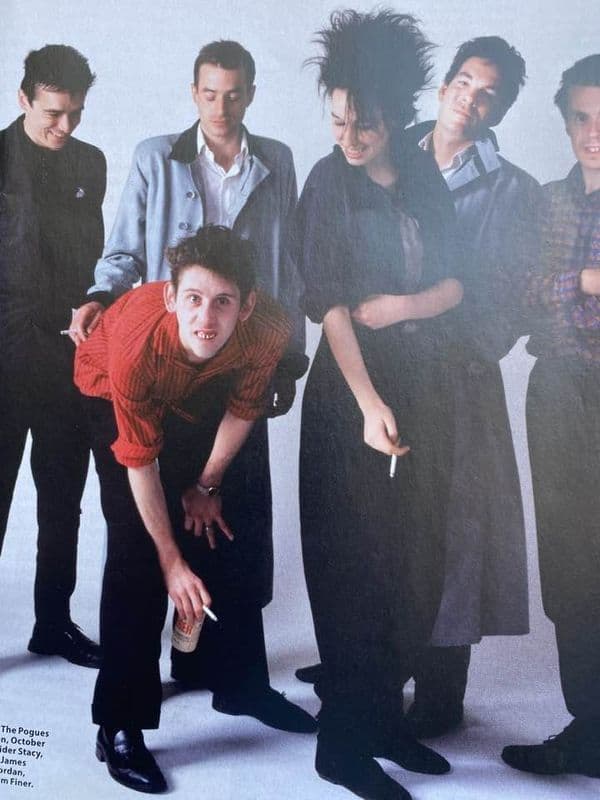

To understand this song is to understand the strange alchemy that made The Pogues so vital. Led by the brilliant and chaotic Shane MacGowan, the band fused traditional Irish music with the raw aggression of punk rock. By 1988, they were no longer outsiders playing noisy folk tunes in smoky pubs; they were storytellers with a global audience, carrying centuries of Irish history in battered instruments and weathered voices.

“If I Should Fall From Grace With God” opens with martial drums and blaring horns, immediately evoking the sound of marching — not in triumph, but in defiance. The lyrics are steeped in imagery of exile, rebellion, and spiritual reckoning. MacGowan sings not as a saint, but as a sinner fully aware of his flaws, daring heaven itself to judge him. The “fall from grace” is not a single act, but a lifetime of choices — drinking, fighting, loving fiercely, and living without apology.

At its heart, the song reflects the Irish experience of displacement and resistance. Lines referencing deportation, prisons, and distant lands echo the long history of Irish emigration, particularly to England and America. Yet the tone is not mournful. It is confrontational, even triumphant. The narrator may be cast out, but he refuses to be broken. There is pride in his voice — pride in survival, in identity, in refusing to bow.

Musically, the track is a masterclass in controlled chaos. Traditional instruments like tin whistle and accordion collide with pounding drums and electric energy. It feels ancient and modern at once, as if centuries-old folk melodies have been electrified by anger and hope. This fusion is precisely why the album resonated so deeply in the late 1980s, a time when many listeners were searching for roots without nostalgia, rebellion without emptiness.

The album If I Should Fall from Grace with God also introduced the world to “Fairytale of New York,” further cementing its legacy. But the title track stands as the album’s moral and emotional backbone. It tells the listener exactly who The Pogues are: unpolished, unrepentant, and profoundly human. There is faith here, but it is complicated — faith tested by experience rather than protected by innocence.

For older listeners, the song carries an added weight. It speaks to lives lived fully, sometimes recklessly, often imperfectly. It acknowledges the quiet reckoning that comes with age — the moments when one looks back and asks not whether they were good, but whether they were true. MacGowan does not ask forgiveness; he asks to be understood.

Over the decades, “If I Should Fall From Grace With God” has become a rallying cry at concerts, pubs, and gatherings where memory and music intertwine. It is shouted, sung, and sometimes whispered by those who recognize themselves in its defiance. Not heroes, not villains — just people who lived, loved, and endured.

In the long arc of popular music, this song stands apart. It is not gentle. It does not comfort easily. Yet it offers something rarer: honesty. And for those who have walked long roads, crossed borders visible and invisible, and carried their faith alongside their doubts, “If I Should Fall From Grace With God” remains a powerful reminder that even a fall can be sung with dignity.