A Song About Escape, Desperation, and the Last Turn of the Key Before the Dark

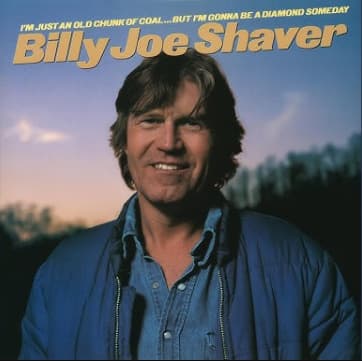

Released in 1981, Ragged Old Truck stands as one of the most raw and unsettling songs in the catalog of Billy Joe Shaver, a writer whose reputation rests not on polish, but on truth told without mercy. The song appeared on the album I’m Just an Old Chunk of Coal, a record that did not dominate commercial charts but quietly reinforced Shaver’s standing as one of the most honest voices in outlaw country. Ragged Old Truck was never a major Billboard hit, and it never needed to be. Its power has always lived outside chart positions, passed hand to hand through listeners who recognized its truth immediately.

By the time this song was released, Billy Joe Shaver was already respected within songwriter circles as a survivor. His songs had been recorded by Waylon Jennings, Willie Nelson, and Johnny Cash, yet his own life remained chaotic, financially unstable, and emotionally fractured. Ragged Old Truck came from one of the darkest chapters of that life. The song is rooted in a real incident following the collapse of his marriage to Brenda Shaver, when loneliness, guilt, and despair pushed him toward the edge. He spent his remaining money on an old truck that would not start, a bitterly symbolic purchase that mirrored how trapped he felt inside his own circumstances.

The story behind the song goes further than simple heartbreak. Shaver later spoke openly about contemplating suicide during that period, even engaging in a reckless game of Russian roulette with an automatic pistol. These were not metaphors. They were lived moments. Ragged Old Truck was written afterward, not as a dramatization, but as a form of emotional purging. Writing the song allowed him to step back from the ledge and translate chaos into narrative. That is what gives the song its unsettling authenticity.

Lyrically, Ragged Old Truck tells the story of a man suffocating inside routine and domestic confinement. The phrase “choking” is not incidental. It reflects emotional strangulation rather than marital resentment. When the narrator decides to crank up his truck, drive into town, and “raise so doggone much hell” before his wife returns from Waco, it is not an act of rebellion for pleasure. It is survival. The truck becomes both an escape vehicle and a last lifeline. It is ragged, unreliable, barely functional, yet it represents motion. And motion, however dangerous, feels preferable to standing still.

Musically, the song is stripped down and unadorned. The melody follows traditional country phrasing, but the delivery carries a bruised urgency. Shaver’s voice is weathered, imperfect, and emotionally exposed. There is no attempt to soften the message or romanticize the behavior. The recklessness is presented plainly, without apology or justification. That restraint is part of the song’s moral weight.

Within the broader context of outlaw country, Ragged Old Truck occupies a unique position. Where many outlaw songs celebrate defiance, Shaver’s song documents its cost. Freedom here is not triumphant. It is desperate, temporary, and shadowed by regret. The song reflects a generation of writers who understood that escape often comes with consequences, and that the road does not always lead to redemption.

Over the decades, Ragged Old Truck has endured because it speaks to moments people rarely confess out loud. It captures the private hour when responsibilities feel unbearable and impulse whispers louder than reason. The song does not ask for sympathy, nor does it offer resolution. It simply tells the truth as it happened, leaving the listener to sit with it.

In the end, Billy Joe Shaver did turn his life around, at least enough to keep writing, recording, and telling his stories until the very end. Ragged Old Truck remains as a document of the moment before that turn, when the engine would not start, the money was gone, and the future looked impossibly narrow. It is not a song of escape. It is a song of standing at the edge and choosing, somehow, to stay.