A wild celebration of youth, rhythm, and rebellion—“Long Tall Sally” captured the raw energy of early rock ’n’ roll and refused to grow old.

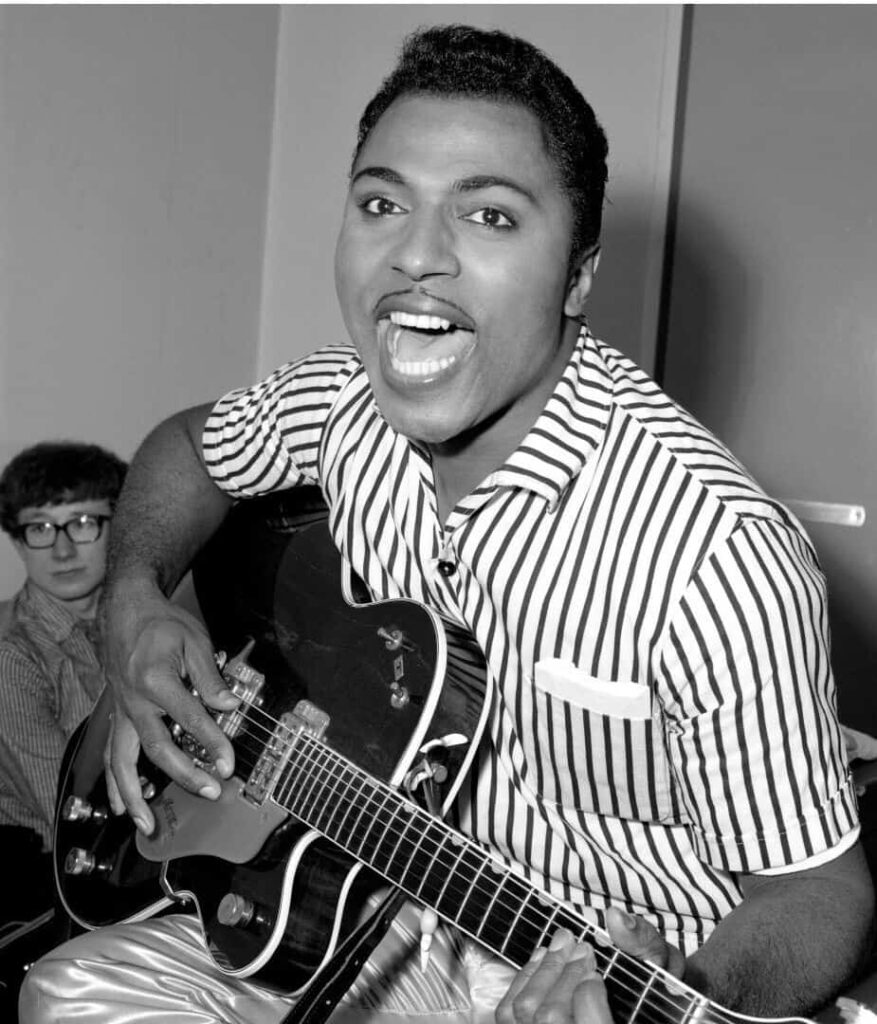

When Little Richard released “Long Tall Sally” in March 1956, popular music was standing at a crossroads. The polite boundaries of rhythm and blues were being shattered by something louder, faster, and far more dangerous. This song did not politely knock on the door of American culture—it kicked it wide open. From its first shouted syllable to its breathless ending, “Long Tall Sally” sounded like freedom in motion, and it announced Little Richard not just as a hitmaker, but as a revolutionary force.

Commercially, the song made an immediate impact. “Long Tall Sally” reached No. 6 on the Billboard R&B Best Sellers chart in 1956 and crossed over to the pop market, peaking at No. 13 on the Billboard pop chart—a remarkable achievement at a time when racial barriers in radio and record sales were still deeply entrenched. In the United Kingdom, where American rock ’n’ roll was just beginning to ignite young imaginations, the song later became a major hit as well, further cementing Little Richard’s international influence.

Behind the song lies a clever and often overlooked story. Co-written by Little Richard, Robert “Bumps” Blackwell, and Enotris Johnson, “Long Tall Sally” was partly designed to outmaneuver censorship. Blackwell has often recalled that the lyrics were intentionally packed with rapid-fire words and playful chaos, making them difficult for conservative radio programmers to fully decipher. Beneath the surface tale of Uncle John, Aunt Mary, and the mysterious Sally, the song carried the kind of sly, adult humor that rhythm and blues had long embraced—but now delivered at breakneck speed.

Musically, “Long Tall Sally” is a masterclass in controlled mayhem. The pounding piano, the relentless backbeat, and Little Richard’s explosive vocal—half scream, half gospel sermon—created a sound that felt barely containable. Unlike many pop songs of its era, there is no gentle build-up, no polite introduction. The listener is thrown directly into the action, as if stumbling into a crowded dance hall where the band is already on fire. This urgency became one of the defining traits of early rock ’n’ roll.

The song’s meaning goes beyond its playful narrative. “Long Tall Sally” represents youth refusing to sit still. It celebrates movement, desire, and release in a world that often demanded restraint. For many listeners in the mid-1950s, this music felt like a secret language—something alive and honest that belonged to them, not to institutions or traditions. That feeling has never entirely faded.

Its legacy is impossible to overstate. The Beatles famously used “Long Tall Sally” as a showstopper in their early live sets, with Paul McCartney pushing his voice to its limits in homage to Little Richard. Elvis Presley, Buddy Holly, and countless others absorbed its lessons: sing louder, play harder, mean every note. The song became a rite of passage for rock singers who wanted to prove their fire.

Today, listening to “Long Tall Sally” is like opening a time capsule—but one that still feels dangerous. It reminds us of a moment when music was not yet polished or safe, when three minutes could feel like a small rebellion. Little Richard, with his towering presence and uncontainable spirit, did more than record a hit; he carved out space for generations to come.

In the end, “Long Tall Sally” endures because it sounds alive. It does not ask for nostalgia—it creates it. And every time that piano starts to pound and that voice takes off, it carries listeners back to a time when the world seemed ready to change at the speed of a song.