A Song of Regret, Freedom, and the Echo of a Distant Train: How “Folsom Prison Blues” Still Rides the Rails of American Memory

When Brandi Carlile takes on “Folsom Prison Blues,” she is not merely covering a song—she is stepping into one of the most enduring myths of American music. Before her voice ever wraps around that famous opening line—“I hear the train a comin’…”—the weight of history is already in the room.

It is important to begin where the story truly starts: with Johnny Cash. Written in the early 1950s and first recorded in 1955 for Sun Records, “Folsom Prison Blues” did not initially become a national pop smash. Its legend grew gradually. The definitive moment came in 1968, when Cash recorded it live inside California’s Folsom State Prison for the album At Folsom Prison. That live version was released as a single and reached No. 1 on the Billboard Hot Country Singles chart in 1968, where it remained for four weeks. It also crossed over to the mainstream, peaking at No. 32 on the Billboard Hot 100, and climbed to No. 3 on the UK Singles Chart. At the 1969 Grammy Awards, the song earned nominations for Best Country Vocal Performance, Male and Best Country Song, sealing its place in American musical canon.

The story behind the song is as stark as its opening guitar riff. Cash was inspired, in part, by the 1951 film Inside the Walls of Folsom Prison and by his own deep empathy for society’s outsiders. The lyric—“I shot a man in Reno just to watch him die”—is one of the most chilling lines ever to slip into popular music. It is not autobiographical confession but dramatic storytelling, delivered with such conviction that it feels like lived experience. That was Cash’s gift: he sang not as a judge, but as a witness. In a country wrestling with questions of justice, guilt, and redemption, “Folsom Prison Blues” became an anthem for the forgotten.

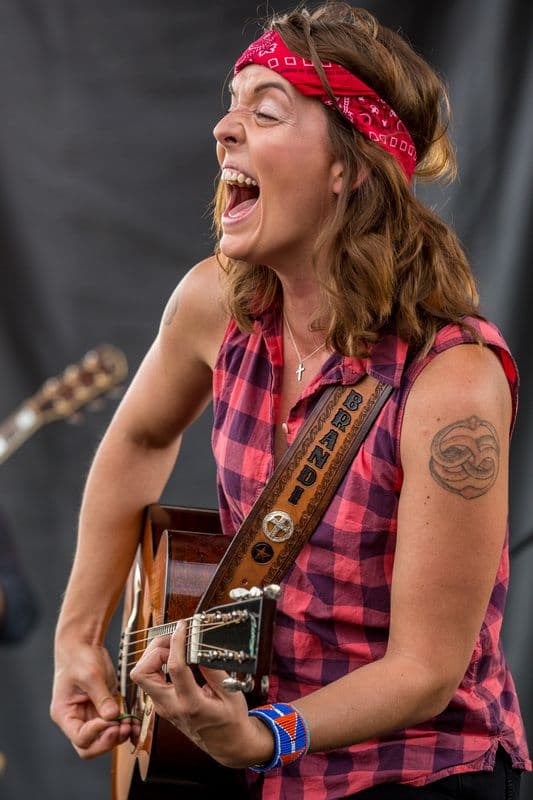

Decades later, when Brandi Carlile performs the song—most notably during the 2018 Grammy Salute to Music Legends honoring Johnny Cash—she does so with reverence but without imitation. Carlile does not try to replicate Cash’s baritone gravity. Instead, she brings a tensile strength, a controlled fire. Her voice carries both ache and defiance, as if she understands that the prison in the song is not only made of concrete and steel, but of regret.

Carlile’s interpretation reminds us that the song’s power lies in its restraint. The famous “boom-chicka-boom” rhythm, first shaped by Luther Perkins’ guitar, is deceptively simple. Underneath it runs the metaphor of the train—freedom in motion, always just out of reach. When Carlile leans into the melody, she emphasizes that contrast: the stillness of confinement against the unstoppable passage of time. It becomes less a tale of crime and more a meditation on consequence.

What makes “Folsom Prison Blues” so enduring is its emotional honesty. There is no moral sermon, no tidy resolution. The narrator listens to the train and imagines a world moving on without him. That image has resonated for generations because it speaks to something universal—the fear of being left behind, the weight of one irrevocable mistake. In an era when songs were often polished and romantic, this was raw and unvarnished.

For listeners who remember hearing the live At Folsom Prison album crackle through a vinyl speaker, the song carries the atmosphere of that prison yard—the cheers, the nervous laughter, the electricity of a man confronting his audience with their own story. When Carlile revisits it, she does not disturb that memory; she extends it. She reminds us that great songs are not museum pieces. They breathe differently in each generation.

In the end, Brandi Carlile’s “Folsom Prison Blues” is less about reinterpretation and more about continuity. It affirms that the song’s central themes—freedom, remorse, longing—remain as relevant now as they were in 1968. The train is still coming. The whistle still blows. And somewhere between those notes, we hear not only Johnny Cash’s shadow, but our own reflections moving through time.