A Joyful Cry for Unity in Divided Times

When Three Dog Night released “Black and White” in 1972, they didn’t simply deliver another radio hit—they captured the moral heartbeat of a restless America. The song soared to No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100 in September 1972, becoming the group’s third chart-topper and one of the defining pop statements of the early 1970s. It also reached No. 1 in Canada and climbed high across international charts, confirming that its message transcended borders. At a time when the airwaves were crowded with soft rock and polished pop, “Black and White” stood out for its unapologetic optimism and moral clarity.

Originally written and recorded in 1954 by David I. Arkin and Earl Robinson, the song was first associated with the American folk revival. Robinson, known for his socially conscious compositions, crafted the melody around Arkin’s lyrics—a lyrical plea for racial harmony inspired by the landmark 1954 Supreme Court decision Brown v. Board of Education, which declared racial segregation in public schools unconstitutional. The song’s origins were deeply rooted in the civil rights struggle, long before it became a pop anthem. In 1970, reggae group Greyhound had a hit with it in the UK, but it was Three Dog Night’s buoyant 1972 version that etched it permanently into mainstream American memory.

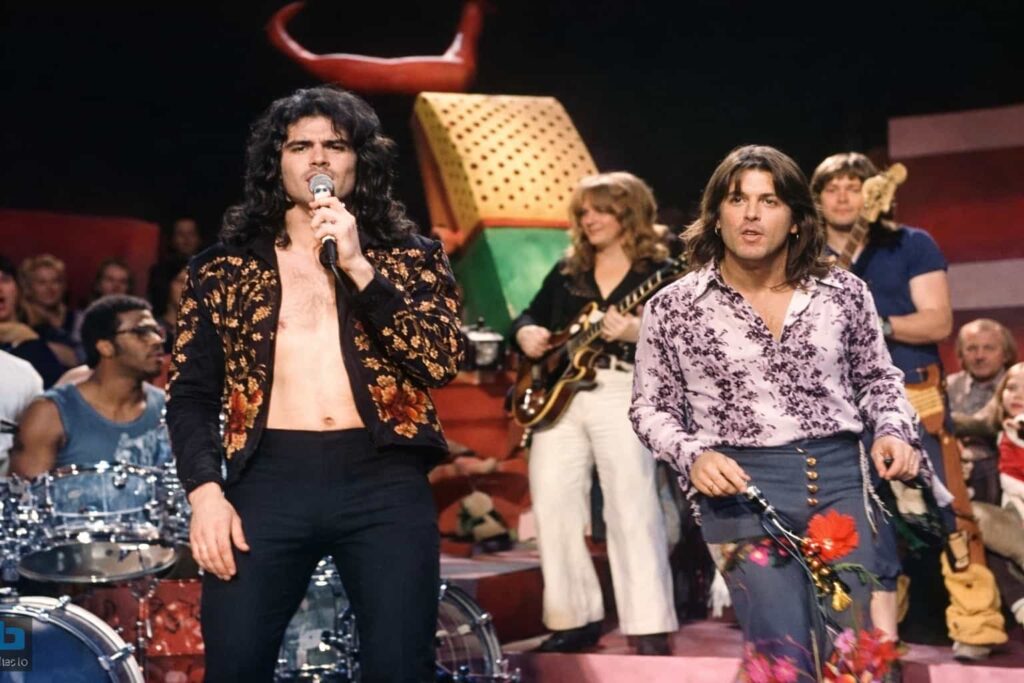

Produced by Richard Podolor and featured on the album Seven Separate Fools, the band’s arrangement replaced folk simplicity with bright, punchy instrumentation and an infectious, almost childlike exuberance. Lead vocalist Danny Hutton delivered the verses with an earnest clarity that felt both intimate and universal. The handclaps, driving rhythm section, and gospel-tinged backing vocals created a sense of communal celebration. This was not protest music steeped in anger; it was a hopeful affirmation, sung with conviction that unity was not just possible—it was inevitable.

By 1972, the United States was still grappling with the aftershocks of the civil rights movement. The optimism of the 1960s had been bruised by political scandals, Vietnam, and social unrest. Yet “Black and White” radiated a simple but powerful refrain: “The ink is black, the page is white / Together we learn to read and write.” Its metaphor was disarmingly straightforward. The page and the ink, distinct yet inseparable, symbolized coexistence. The classroom imagery reminded listeners that change begins with the young—and that prejudice is not innate but taught. In that sense, the song felt like both a lullaby and a lesson.

What made Three Dog Night’s version so effective was their ability to balance seriousness with warmth. The band—already established through hits like “Joy to the World” and “Mama Told Me (Not to Come)”—understood how to translate socially resonant material into radio-friendly gold. Their three lead vocalists—Danny Hutton, Cory Wells, and Chuck Negron—had built a reputation for rich harmonies and interpretive strength. On “Black and White,” they leaned into simplicity, allowing the melody and message to breathe. The result was a song that felt less like a lecture and more like a shared memory waiting to happen.

Over the decades, “Black and White” has remained one of those songs that instantly evokes a particular emotional landscape. It recalls school assemblies, transistor radios humming on kitchen counters, and the quiet belief that music could help heal divisions. It carries the spirit of an era when pop music dared to speak directly about social justice yet still aimed for the top of the charts. The fact that it reached No. 1 speaks volumes—not just about its catchy arrangement, but about the appetite listeners had for hope.

Listening today, the song feels both time-stamped and timeless. Its production unmistakably belongs to the early ’70s, with its crisp percussion and layered vocals. Yet its message remains painfully relevant. The beauty of “Black and White” lies in its refusal to complicate what is fundamentally simple: equality is not a radical idea; it is a moral one.

For many, the song represents more than a chart achievement. It stands as a reminder of how popular music once carried civic weight without losing its melodic charm. In the hands of Three Dog Night, a folk protest tune became a joyous pop declaration—a reminder that even in uncertain times, harmony is not just something we sing. It is something we strive to live.