A Bitterly Humorous Portrait of Vanishing Chicago and the People Left Behind

Few songs capture the soul of a city with as much wit, irony, and quiet melancholy as “Lincoln Park Pirates” by Steve Goodman. Released in 1972 on his self-titled debut album Steve Goodman, the song stands as one of the sharpest pieces of urban folk satire of its era. Although it did not chart on the Billboard Hot 100—nor was it intended as a commercial single—it became a cult classic in Chicago and among folk aficionados, solidifying Goodman’s reputation as one of America’s most perceptive singer-songwriters. More importantly, it revealed his remarkable ability to transform a local grievance into a universal meditation on change, loss, and the small indignities of modern life.

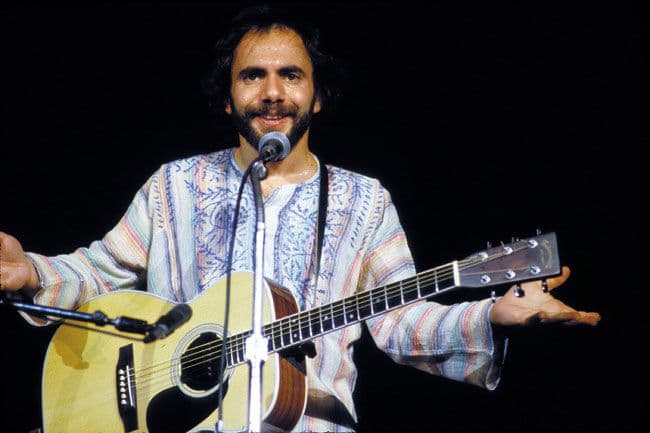

To understand the song, one must first understand the man. Steve Goodman emerged from Chicago’s vibrant folk scene in the late 1960s, a contemporary and friend of John Prine. Goodman possessed a unique blend of humor and poignancy; his best-known composition, “City of New Orleans”, would later become a hit for Arlo Guthrie, reaching No. 18 on the Billboard Hot 100 in 1972. But if “City of New Orleans” was his wistful ballad of fading railroads, then “Lincoln Park Pirates” was his sardonic protest against another kind of disappearance—one not of trains, but of fairness and community spirit.

The “pirates” of the title were Lincoln Towing Service, a real Chicago towing company notorious in the late 1960s and early 1970s for aggressively towing cars from the Lincoln Park neighborhood. Goodman himself was reportedly a victim. The song’s opening lines immediately set the tone: sharp, funny, almost playful. Yet beneath the humor lies genuine frustration. Goodman sings from the perspective of an ordinary citizen caught in the bureaucratic absurdity of retrieving a towed car—an ordeal that becomes symbolic of powerlessness in the face of faceless authority.

Musically, the arrangement is deceptively simple. Driven by brisk acoustic guitar and Goodman’s nasal, conversational vocal delivery, the song borrows from the talking-blues tradition. There’s an undercurrent of ragtime bounce, almost inviting the listener to tap a foot while absorbing lyrics that sting with social commentary. The melody is light; the message is not.

What makes “Lincoln Park Pirates” endure is not merely its local specificity, but its emotional undercurrent. On the surface, it is comic storytelling. But as the verses unfold, it becomes clear that Goodman is chronicling more than a parking dispute. He is documenting a city in transition—neighborhoods gentrifying, institutions hardening, ordinary people feeling squeezed out. The song becomes a snapshot of urban America in the early 1970s, when trust in authority was fraying and communities were shifting beneath familiar feet.

There is something especially poignant about the way Goodman uses humor as armor. Rather than rage, he chooses wit. Rather than sermonize, he narrates. The listener laughs—but also recognizes the sting of recognition. Many have known that sinking feeling of helplessness when confronted with bureaucracy. Goodman understood that small injustices often feel the most personal.

In retrospect, the song carries additional weight because of Goodman’s own life story. Diagnosed with leukemia as a teenager, he lived with an acute awareness of time’s fragility. That awareness often infused his songwriting with urgency and tenderness. Even in a satirical piece like “Lincoln Park Pirates,” one senses his deep affection for Chicago and its people. The frustration comes not from cynicism, but from love.

Over the decades, the song has remained a Chicago anthem of sorts, occasionally revived in local discussions about towing practices and city politics. It represents a kind of folk journalism—music as documentation. While it never occupied a space on national charts, its cultural resonance in the Midwest has been profound. In folk circles, it is frequently cited as one of Goodman’s sharpest compositions.

Listening to Steve Goodman sing “Lincoln Park Pirates” today, one hears more than a clever protest song. One hears the voice of a young artist observing his world with clear eyes and a mischievous smile. The details may belong to 1970s Chicago, but the feeling—the sense of watching something familiar slip away—is timeless.

And perhaps that is why the song still resonates. Cities change. Systems grow impersonal. Ordinary people navigate rules that rarely seem designed for them. Yet through it all, there remains the possibility of telling the story—of turning frustration into song. Goodman did just that, leaving behind not merely a complaint, but a living document of a place, a moment, and a spirit that refuses to be towed away.