An Evocative, Soulful Plea for Equality: Reflecting on the Lingering Disappointment of the Civil Rights Dream.

Oh, the mid-1970s! A time when the echoes of the vibrant, tumultuous ’60s were still ringing, but perhaps with a slightly hollow tone. It was into this complex cultural landscape that Frank Zappa, the maestro of the unconventional, released his watershed album, Apostrophe (‘), in March 1974. Though “Uncle Remus” was never a charting single itself—that distinction belonged to the album’s quirky opener, “Don’t Eat the Yellow Snow,” which peaked at a surprising No. 86 on the Billboard Hot 100—its parent album, Apostrophe (‘), achieved a commercial success that was truly unprecedented for Zappa, soaring all the way to Number 10 on the US Billboard 200 chart. This was the highest chart placement of his career, a sign that the mainstream was, however briefly, ready to listen to the Mothers of Invention’s eccentric former leader.

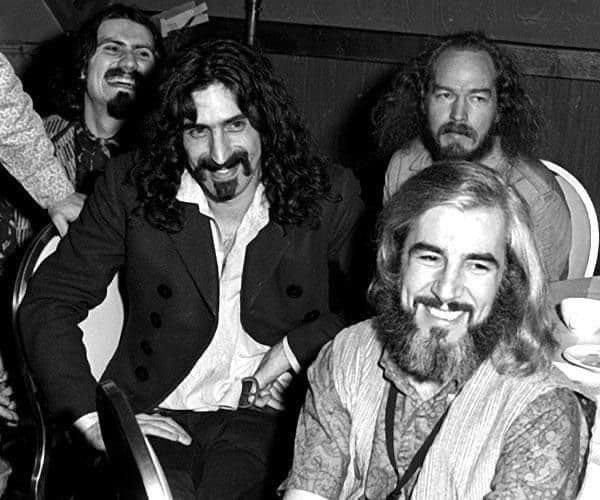

Apostrophe (‘) is often remembered for its absurdist humor and musical virtuosity, yet tucked away on the album’s second side is “Uncle Remus,” a surprisingly earnest, soulful, and pointed piece of social commentary that stands as one of Zappa‘s most heartfelt statements on race in America. This song is a departure from Zappa‘s usual biting satire, taking on a tone of lament and somber reflection. The story behind the song is a fascinating example of collaboration, as the lush, gospel-infused music was actually composed by keyboardist George Duke, a pivotal figure in jazz-funk and fusion, who co-wrote the piece. Duke had recorded a demo of the music, and Zappa was so impressed that he decided to use the track for his album, penning the deceptively simple, yet deeply layered, lyrics himself. This blending of Duke‘s soulful, jazz-rock musicality with Zappa‘s razor-sharp lyrical intellect creates a unique, poignant mood unlike much of Zappa‘s catalogue.

The meaning of “Uncle Remus” delves into the stalled, frustrating reality of the Civil Rights movement in the early 1970s. The narrator, a young Black man, is seen standing on a street corner in a presumably affluent, white neighborhood—a detail driven home by the specific, scathing line about Beverly Hills. The lyrics juxtapose a desire for personal dignity and cultural expression (“I can’t wait till my Fro is full-grown / I’ll just throw ’way my Doo-Rag at home”) with the enduring legacy of institutional racism and demeaning, casual prejudice. The chilling line about being “sprayed with a hose / While I’m lookin’ sharp in these clothes” is a direct, undeniable reference to the horrifying images of civil rights protestors being attacked with water cannons in the 1960s.

The central, most moving query of the song is contained in the chorus, sung with an almost heartbreaking sincerity by George Duke: “Are we moving too slow?” It’s a profound question that hangs in the air, a realization that the grand promises of equality had not been fully realized, and that the fight was far from over. The song also targets the superficiality and hypocrisy of the wealthy elite by focusing on the ‘lawn jockeys’—the racially offensive, stereotypical statues often displayed on the lawns of rich white Americans. The youthful fantasy of “knockin’ the lawn jockeys off the front porch” becomes a powerful symbol of frustrated, symbolic protest in the face of systemic inertia.

For those of us who lived through that era, the song resonates with a nostalgic melancholy. It reminds us that Zappa, often perceived as a cynic, had a deep, moral core and a willingness to tackle serious issues without resorting to his typical cartoonish excess. It is a moment of raw, musical beauty on an album celebrated for its irreverence, and a timeless reminder that the march toward true equality is, regrettably, always a marathon, never a sprint.