Dark Star — when silence, memory, and cosmic sound meet in the hands of a quiet master

When Garth Hudson turns toward “Dark Star,” he is not chasing a song so much as stepping into a universe. This is not the familiar rock epic driven by vocals and spectacle; it is an inward journey, guided by breath, space, and tone. Hudson’s interpretation appears on his 2001 solo album The Sea to the North, a record that stood apart from commercial ambition and, accordingly, never entered mainstream charts upon release. Yet its importance lies elsewhere — in artistry, restraint, and the rare courage to let music speak without explanation.

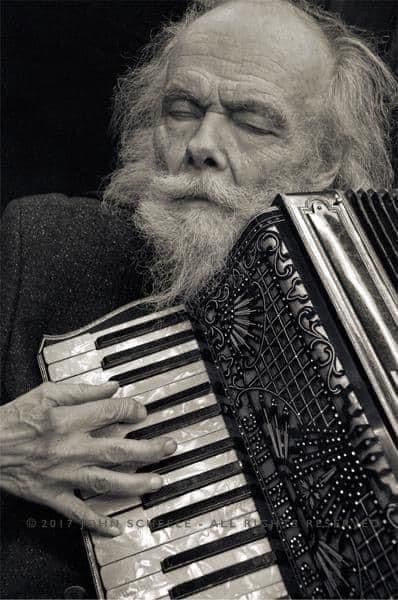

Before anything else, it must be said clearly: Garth Hudson was never an ordinary member of The Band. While others stood at the front, he remained seated behind a constellation of keyboards, shaping atmosphere rather than demanding attention. Classically trained, deeply curious, and instinctively experimental, Hudson brought an almost orchestral sensibility into American roots music. By the time he recorded The Sea to the North, he was no longer interested in song structures that needed to resolve. He was interested in memory, landscape, and sound as emotion.

“Dark Star” — originally associated with the Grateful Dead — becomes something entirely different in Hudson’s hands. Stripped of lyrics, stripped of jam-band bravado, it turns into a meditative, instrumental reflection. The accordion and keyboards do not announce themselves; they hover, drift, and pulse gently, like distant constellations slowly rotating in a night sky. This is music that does not move forward so much as it expands outward.

The story behind Hudson recording this piece is inseparable from his lifelong relationship with improvisation. He had always believed that music should breathe, that silence was as important as sound. On The Sea to the North, he assembled a group of musicians who understood restraint — players willing to listen more than they played. “Dark Star” emerges from that philosophy: a quiet conversation among instruments, guided by intuition rather than arrangement.

For listeners who have lived long enough to appreciate understatement, the meaning of this piece reveals itself gradually. It is not about drama or climax. It is about space — the kind that opens after years of experience, after joy and disappointment have settled into something calmer. Hudson’s version of “Dark Star” feels like looking back at a long life from a distance, seeing patterns instead of details, accepting mystery instead of answers.

There is also a sense of farewell woven into the performance. Not a goodbye to people, but to eras. By 2001, much of the world that had shaped Hudson’s early career was gone or transformed. The optimism of the late 1960s, the communal spirit of experimentation, the belief that music could quietly change consciousness — all of it lingered only in echoes. “Dark Star” becomes a vessel for those echoes.

What makes the piece especially moving is its humility. Hudson never tries to claim ownership of the composition. Instead, he treats it as a shared memory — something borrowed, honored, and gently reshaped. The melody surfaces and disappears like a thought you almost remember, then let drift away. For older listeners, this sensation feels familiar. It mirrors how memory itself works: not linear, not precise, but deeply emotional.

Commercial success was never part of the equation. The Sea to the North was released quietly, received respectfully, and treasured mostly by those who were willing to listen closely. Yet “Dark Star” stands today as one of Hudson’s most revealing performances — not because of virtuosity, but because of wisdom.

In the end, this is music for late hours and low light. Music for reflection rather than celebration. Garth Hudson’s “Dark Star” reminds us that some of the most meaningful journeys do not need words, and some of the deepest emotions reveal themselves only when the world grows quiet enough to hear them.