A quiet meditation on rural labor, fading landscapes, and the dignity of lives rarely turned into songs

When James McMurtry released “Canola Fields” in 2008, it did not arrive with the noise or ambition of a hit single. There was no rush to radio, no bid for the Billboard Hot 100, and no expectation that the song would compete in the commercial charts of its day. In fact, “Canola Fields” was never issued as a chart-seeking single at all. Instead, it appeared as one of the emotional and narrative anchors of Just Us Kids (2008), an album that quietly entered the Billboard Top Heatseekers and the Americana/Folk album listings, earning strong critical attention rather than mass-market numbers. That context matters, because McMurtry has always written for listeners, not demographics.

“Canola Fields” is rooted in McMurtry’s long-standing fascination with rural America—not the romanticized version, but the working landscape shaped by agriculture, exhaustion, and endurance. The song takes its name from the bright yellow canola crops that briefly transform otherwise flat farmland into something almost luminous. Yet the beauty here is fleeting. McMurtry uses the fields as a visual counterpoint to the emotional fatigue of the people who move through them, work beside them, and grow older watching them return year after year.

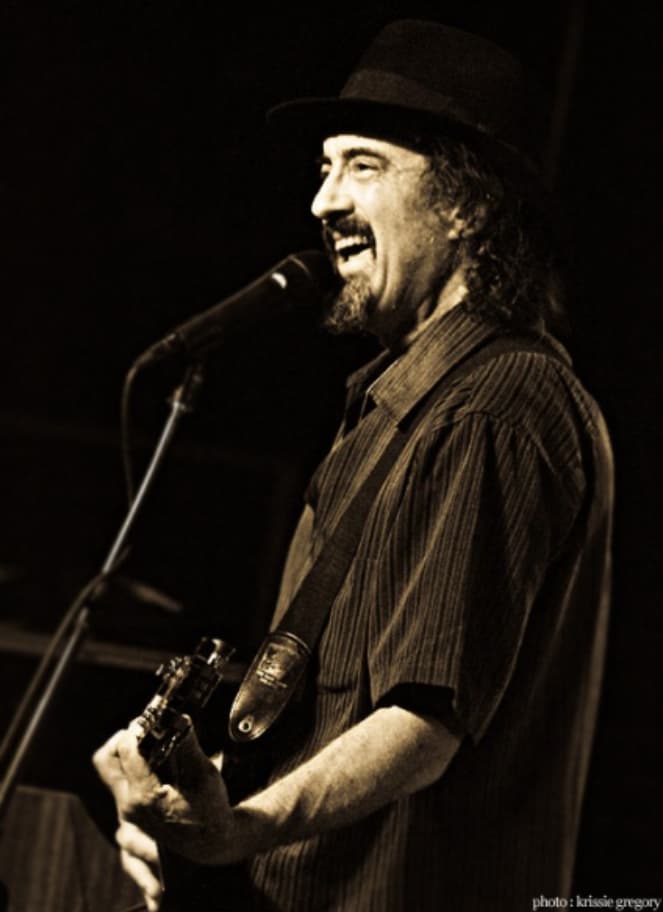

Musically, the song sits firmly in McMurtry’s restrained Americana style. The arrangement is spare and unforced, allowing the lyric to carry the weight. There are no dramatic crescendos, no sweeping gestures—just a steady, grounded delivery that mirrors the physical rhythm of farm labor and long drives down rural highways. McMurtry’s voice, dry and conversational, never pleads for attention. It assumes the listener is willing to lean in.

The story behind “Canola Fields” is not a single anecdote but an accumulation of observation. McMurtry has often spoken about writing from fragments—overheard conversations, remembered places, half-seen lives. Here, the song feels like it emerges from years of watching small towns hollow out, farms consolidate, and relationships quietly strain under economic pressure. The narrator does not dramatize these changes. He reports them, almost reluctantly, as facts of life.

Lyrically, the song is about distance—between people, between generations, and between what once seemed possible and what remains. The canola fields glow briefly, almost mockingly, against the backdrop of emotional resignation. McMurtry avoids nostalgia for its own sake. There is no longing for a lost golden age, only an acknowledgment that time moves forward whether people are ready or not. This refusal to sentimentalize is precisely what gives the song its emotional power.

Within Just Us Kids, “Canola Fields” functions as a moment of stillness. The album as a whole wrestles with inheritance—personal, cultural, and political—and the uneasy knowledge of what gets passed down. In that sense, the song’s meaning extends beyond agriculture. The fields become symbols of routines inherited without question, of lives shaped by geography as much as choice.

What makes James McMurtry so distinctive here is his restraint. Lesser writers might have underlined the message, or reached for a chorus designed to console. McMurtry does neither. He trusts the listener to sit with discomfort, to recognize pieces of their own history in the quiet spaces between lines. The song does not offer resolution. It offers recognition.

Over time, “Canola Fields” has grown in stature among listeners who value songwriting as literature. It is often cited by longtime fans as one of McMurtry’s most quietly devastating works—not because it shocks, but because it feels true. In an era increasingly dominated by speed and spectacle, the song stands as a reminder that some stories only reveal themselves slowly, like fields that bloom once a year and then return to dust.

In the end, “Canola Fields” is less about a place than about the passage of time within it. It honors lives lived without applause, moments that never make headlines, and the dignity found in simply carrying on. For those willing to listen closely, it remains one of James McMurtry’s most enduring and humane reflections on the American landscape.