A Quiet Protest in Plain Words: How “We Can’t Make It Here” Turned Everyday American Lives into a Moral Reckoning

When James McMurtry released “We Can’t Make It Here” in 2005, it did not arrive with the fanfare of a mainstream hit, nor was it designed to chase radio trends. Instead, it entered the world quietly, like a hard truth spoken at a kitchen table late at night. The song appeared on his album Childish Things (Columbia Records, 2005), a record that would later be widely regarded as one of the most politically incisive and emotionally grounded Americana albums of the early 21st century. While “We Can’t Make It Here” did not storm the pop charts, it received significant airplay on American Adult Alternative and Americana radio formats and became one of McMurtry’s most discussed and enduring compositions—valued not for chart position, but for its moral weight and lasting relevance.

At the time of its release, Childish Things reached the Top 10 on the Billboard Top Heatseekers chart and entered the Billboard Top 40 Independent Albums, a respectable showing that reflected McMurtry’s standing as a songwriter’s songwriter rather than a commercial celebrity. Yet among critics and long-time listeners, “We Can’t Make It Here” quickly emerged as the emotional and intellectual center of the album—a song that felt less like entertainment and more like testimony.

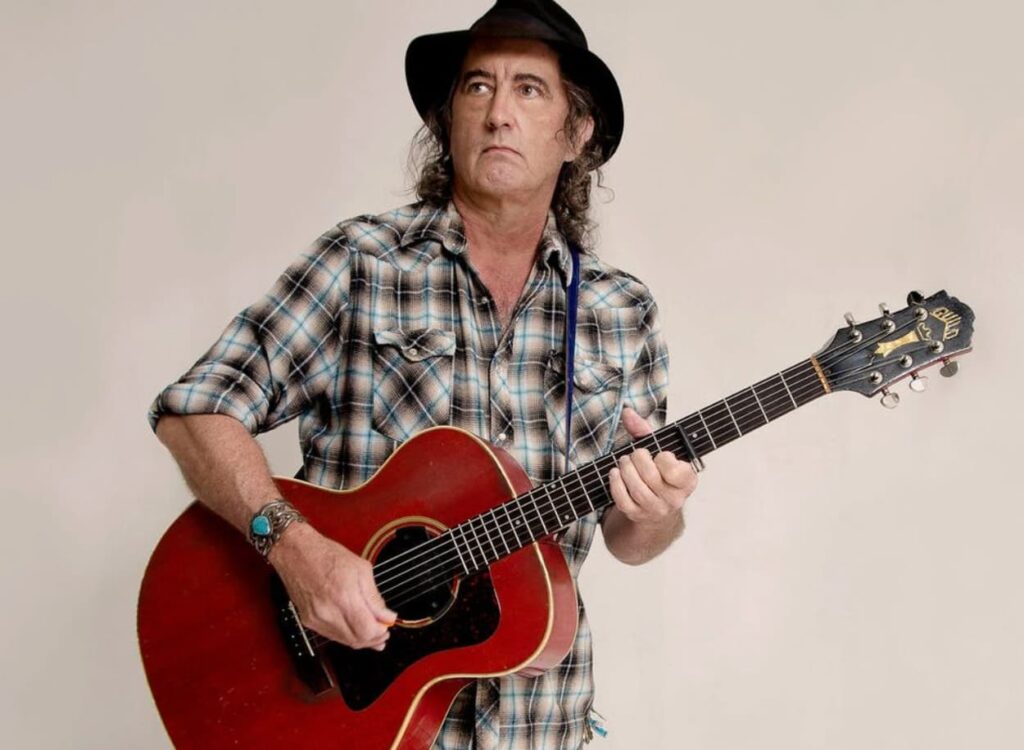

The story behind “We Can’t Make It Here” is rooted in observation rather than ideology. James McMurtry, son of novelist Larry McMurtry, has always written with a novelist’s eye: concrete details, unadorned language, and an instinct for what people do not say out loud. In the early 2000s, as factories closed, wages stagnated, and overseas wars dominated headlines, McMurtry began noticing a widening gap between patriotic rhetoric and lived reality. This song was his response—not as a protest chant, but as a series of scenes drawn from ordinary American life.

Lyrically, “We Can’t Make It Here” unfolds like a slow drive through a forgotten town. There are laid-off workers, exhausted soldiers returning from foreign wars, immigrants blamed for economic collapse, and politicians offering hollow reassurances. McMurtry never raises his voice. He does not preach. Instead, he repeats the devastating refrain—“We can’t make it here anymore”—as if stating an undeniable fact. The power of the song lies precisely in this restraint. By refusing melodrama, McMurtry allows the listener’s own memories and experiences to fill in the emotional gaps.

Musically, the song is built on a restrained, steady groove—electric guitars held in check, a rhythm section that moves forward without urgency or comfort. This sonic understatement mirrors the lyrical theme: lives continuing not because things are hopeful, but because stopping is not an option. The arrangement recalls classic American roots rock, echoing artists like John Prine, Steve Earle, and Townes Van Zandt, yet McMurtry’s voice remains distinct—cool, observational, and quietly unforgiving.

The deeper meaning of “We Can’t Make It Here” lies in its refusal to assign simple blame. While the song touches on immigration, war, and economic displacement, it ultimately speaks to disillusionment—the slow erosion of faith in promises once believed. For listeners who have lived long enough to see cycles of boom and bust, hope and disappointment, the song resonates not as a political statement, but as a human one. It acknowledges a shared exhaustion, a sense that something essential has slipped away, even if no one can say exactly when.

Over the years, “We Can’t Make It Here” has aged with unsettling grace. What felt timely in 2005 has since come to feel prophetic. Yet its lasting impact is not rooted in prediction, but in empathy. James McMurtry does not write from above his subjects; he stands among them, reporting what he sees with clear eyes and an unguarded heart.

In the end, “We Can’t Make It Here” remains one of those rare songs that grow heavier, not lighter, with time. It does not ask the listener to agree or disagree. It simply asks them to remember—what was promised, what was lost, and what it feels like to keep going anyway.