“Daydream Believer” – a wistful ode to the fragile promise of everyday love

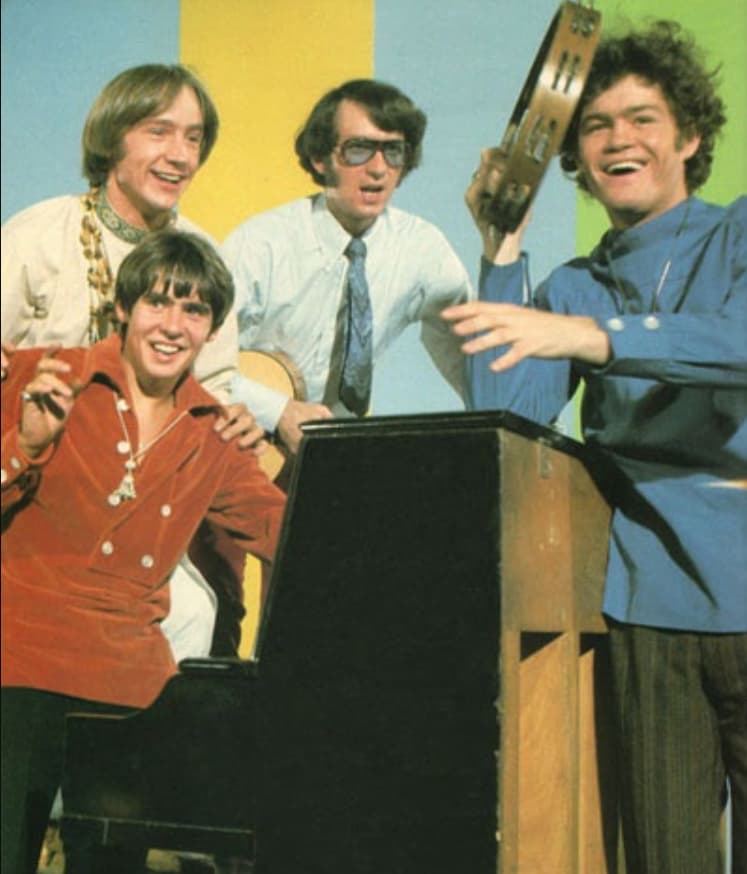

When the bright‑chime of the chorus of Daydream Believer rises in the air, so too do memories of simpler times—of elusive dreams wrapped in the routine of days, of the quiet shift from hope to acceptance. This was the final No. 1 hit for the band The Monkees, topping the U.S. Billboard Hot 100 in December 1967 and holding the summit for four consecutive weeks. In the United Kingdom it climbed up to No. 5.

From the very opening moments—when Davy Jones speaks the line “7 A – what number is this, Chip? 7 – A, okay don’t get excited, man…”—we’re plunged into a moment of studio intimacy and playful routine. The song, penned by folk‑songwriter John Stewart just after his departure from the respected folk ensemble The Kingston Trio, was written as part of a suburban trilogy about the quiet ennui of everyday life. Stewart recalled:

“I remember writing ‘Daydream Believer’ very clearly … I remember thinking ‘What a wasted day — all I’ve done is daydream.’ And from there I wrote the whole song.”

Yet, the story the song tells is more bittersweet than such an easy frame might suggest. The melody is light, jaunty, inviting even—but the lyrics hint at something just slipping away. The protagonist reminisces about how his partner once thought of him as “a white knight on his steed,” and now he asks, “Now you know how happy life can be / Oh … what can it mean to a daydream believer / And a home‑coming queen?” That image—the home‑coming queen, the emblem of once celebrated youth—carries with it the weight of change.

Stewart originally had the line “Now you know how funky life can be,” but the label insisted on changing “funky” to “happy,” as they worried “funky” was too risqué for the group’s clean pop image. So the song quietly shifts from a hint of gritty realism to a more benign wistfulness—but perhaps that only deepens the sense of something unspoken.

One of the lovely ironies in the song’s history is that it was not intended to be the A‑side. It was slated as a B‑side until fate intervened: the masters of the intended A‑side weren’t ready in time, so “Daydream Believer” took the top spot. And what a spot it took. Reaching No. 1 in the U.S. and staying there four weeks signalled that, at that moment, the world was ready to sing along with its gentle melancholy and small‑town reflections.

For many of us who grew up in a time when the radio’s dial seemed to promise more than just entertainment—when songs felt like shared memories—this track hits differently. It’s not just about being happy or sad; it’s about the in‑between, the quiet surrender of youthful hope to adult reality. When the voice sings “Cheer up, sleepy Jean,” we can almost imagine a once‑bright girl, maybe a neighbour or beloved friend, whose daylight dreams have settled into dusk‑toned reflection.

In the grand tapestry of 1960s pop, “Daydream Believer” stands as a poignant counterpoint: while its melody is polished and upbeat, its heart is rooted in a longing for what might have been, or perhaps for what can still be glimpsed in a passing moment. The fact that it was the Monkees’ last U.S. No. 1 only adds to its poignancy: a band born of TV and youth‑mania, still capable of delivering something memorable, serene, and quietly profound.