A Spiritual Journey Set to a Joyful Groove – “Shambala” as an Anthem of Hope and Inner Peace

When Three Dog Night released “Shambala” in 1973, it felt less like a simple radio single and more like a warm breeze drifting through the early 1970s—carrying with it longing, optimism, and a quiet spiritual hunger. The song quickly climbed to No. 3 on the Billboard Hot 100 in May 1973 and reached No. 1 in Canada, becoming one of the group’s most beloved hits. It also landed on the Adult Contemporary chart, reinforcing its broad appeal across audiences who had grown up with the band’s unmistakable harmonies. Featured on the album Cyan (1973), “Shambala” would stand as one of the defining tracks of the group’s middle period—after their explosive late-1960s breakthrough, yet still firmly within their golden era.

Interestingly, “Shambala” was written by Daniel Moore, and another version by B.W. Stevenson was released almost simultaneously in 1973. While Stevenson’s interpretation had a gentler, country-tinged warmth, it was Three Dog Night’s version—driven by buoyant rhythm and soulful vocal interplay—that soared highest on the charts. That contrast between versions only deepened the song’s mystique, as if two different roads were leading toward the same distant horizon.

The word “Shambala” itself refers to a mythical kingdom in Tibetan Buddhist tradition—a hidden paradise symbolizing enlightenment, peace, and harmony. In the early 1970s, as America was emerging from the turbulence of the Vietnam War era and navigating cultural shifts, this idea of a spiritual sanctuary resonated deeply. But what makes Three Dog Night’s “Shambala” so enduring is how it translates that lofty spiritual concept into something grounded and immediate. It is not an abstract hymn; it is a road song, a communal chant, a smile shared between strangers.

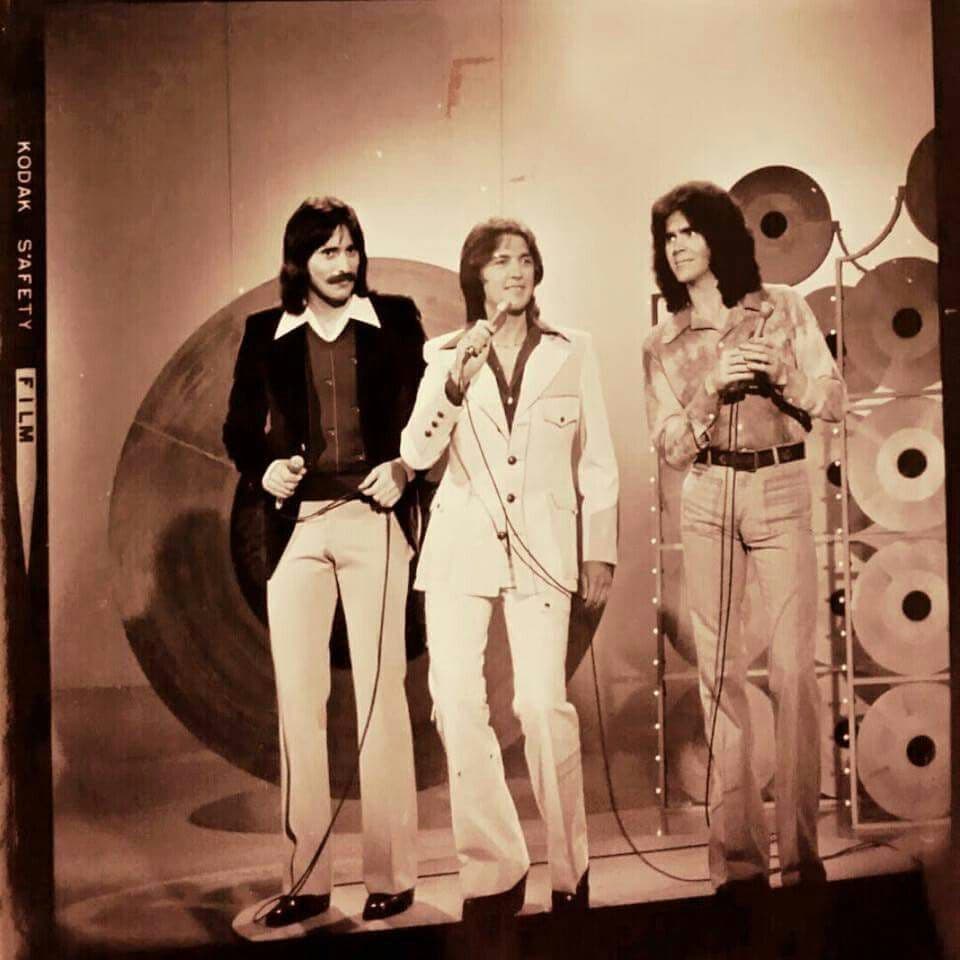

The opening line—“Wash away my troubles, wash away my pain”—is disarmingly simple. Yet when delivered through the warm, textured voice of Cory Wells, supported by the group’s signature three-part vocal blend (Wells, Danny Hutton, and Chuck Negron), it carries the weight of lived experience. Three Dog Night had always excelled at interpreting outside songwriters’ material, turning strong compositions into emotionally resonant radio staples. With “Shambala,” they achieved a rare balance: the groove is light, almost playful, but beneath it flows a current of yearning.

Musically, the track leans into a gospel-infused rock arrangement. The piano-driven rhythm, the rolling percussion, and the communal backing vocals create the feeling of forward motion—like a train heading somewhere better. There is a subtle echo of Southern soul, blended with the polished California pop sensibility that defined much of their catalog. By 1973, Three Dog Night had already amassed a remarkable string of hits—“Joy to the World,” “Mama Told Me (Not to Come),” “Black and White”—and “Shambala” comfortably joined that lineage. It was their 21st Top 40 hit, a testament to their remarkable consistency.

Yet beyond statistics and chart placements, the emotional core of “Shambala” is what lingers. It captures that early ’70s blend of spiritual curiosity and everyday hope. The refrain feels like an invitation—not to a distant, mystical land, but to a state of heart. In live performances, the song often became a moment of collective uplift, audiences swaying gently, singing along as if affirming a shared wish for peace.

Listening today, decades removed from its original chart run, “Shambala” still carries that gentle glow. It reminds us of a time when pop radio could embrace both joy and introspection in the same three-minute space. Three Dog Night were never a band that wrote most of their own hits, but they possessed something equally rare: an instinct for songs that spoke to the moment, and voices capable of turning them into communal experiences.

In the end, “Shambala” endures because it does not preach. It simply suggests that somewhere—whether in a distant mountain kingdom or in the quiet reconciliation of one’s own heart—peace is possible. And sometimes, all it takes is a rolling piano, three intertwined voices, and the courage to believe in a brighter place just up the road.