An Echo from the Trail: The Quiet Heartache of a Cowboy’s Farewell

“I’m Gonna Miss You When You Go” is a tender, yet resigned lament for a love that must be left behind, a quiet note of sorrow in the wide, dusty expanse of the American West.

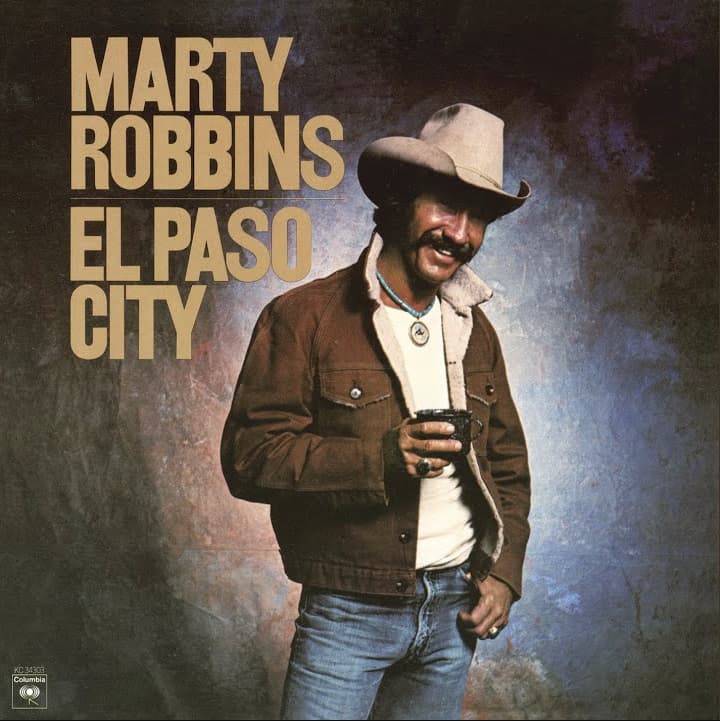

Released in 1976 on the album El Paso City, the song “I’m Gonna Miss You When You Go” by the incomparable storyteller Marty Robbins found its home not as a massive single, but as a crucial piece of a cohesive collection. While the album’s title track, “El Paso City,” itself a sequel to his legendary 1959 hit “El Paso,” soared to Number 1 on the Billboard Hot Country Singles chart, this gentler, self-penned track served a different, more introspective purpose. It didn’t chase the bright lights of the pop chart, instead offering a deeper, more resonant emotional truth that has clung to listeners who appreciate the quiet grace of a classic cowboy song.

Marty Robbins was, first and foremost, a masterful narrator in the tradition of the balladeers of old, and this song is a prime example of his unique ability to set a mood with minimal fuss and maximum impact. It was produced by the legendary Billy Sherrill, who helped shape the sound of country music in the 1970s, but it’s the simple, plaintive vocal and acoustic-leaning arrangement that truly shines through. The track is woven into the fabric of the El Paso City album’s broader theme, which revisits the world of his iconic ‘Gunfighter Ballads.’ While not a direct plot point in the overarching narrative of the doomed cowboy and Feleena from “El Paso,” it exists in that same emotional universe—a world of stoic men, lonely trails, and loves that are as fleeting as a desert rainstorm.

The meaning of “I’m Gonna Miss You When You Go” is one of straightforward, heartbreaking acceptance. It’s not a tale of dramatic gunplay or tragic death, but of a cowboy’s pragmatic reality. The lyrics speak to a man who knows a relationship has reached its end, either through fate, necessity, or the demands of the open road. He’s not pleading or raging; he’s simply acknowledging the deep, quiet ache that comes with severing a bond. “There is no rhyme or reason / To explain the simple why,” he sings, embodying the mature, reflective tone of a man who understands that some things—even the deepest loves—are simply not meant to be. This is a song for those of us who have looked back at a turning point in life, not with regret, but with a wistful longing for something beautiful that time and circumstance forced us to surrender.

For those of us who grew up with the smooth, honeyed baritone of Marty Robbins as the soundtrack to long car rides or quiet evenings, this song is a potent draught of nostalgia. It evokes a time when country music had the space to be cinematic and contemplative, when an artist could paint an entire, fully realized scene in under three minutes. It transports you back to that golden era of the Western genre, whether on the silver screen or in the songs on the radio, where men were expected to be tough, but were still permitted to be vulnerable in the presence of a great melody. Its enduring appeal lies in that shared, universal human experience: the quiet moment when you realize you have to let go of someone you love, and the only comfort is in the honesty of your own sorrow. It’s a reminder that even the toughest trails in life are often paved with the softest heartaches.