A wry little song that turns youthful misadventure into timeless truth about belonging, identity, and the quiet strength of laughing at ourselves.

When Townes Van Zandt first introduced Fraternity Blues to audiences, it entered the world not as a chart contender but as a lived-in story shared from one stage to another. The song was never released as a commercial single, never placed on any Billboard chart, and never sought mainstream attention. Instead, it found its home on the 1977 live double album Live at the Old Quarter, Houston, Texas, a record long regarded as one of the most honest portraits of Van Zandt’s artistry. And though the track list also includes some of his most heartbreaking ballads, this humorous piece stood out as a reminder that even a poet of sorrow could reveal a grin beneath the shadows.

“Fraternity Blues” is, at its heart, a comic monologue set to a lightly strummed guitar. But beneath the jokes about Greek letters, membership dues, hazing rituals, and drunken mishaps, there is a deeper current that long-time listeners often recognize. Van Zandt, known for his gentle spirit and self-effacing intelligence, had always been skeptical of institutions, expectations, and the hollow pursuit of fitting in. The song distills that worldview into a single misadventure: a young man, hoping for acceptance, discovers that conformity is neither flattering nor fulfilling. What emerges instead is a humorous collapse of pretenses, a reminder that belonging must be earned honestly, not purchased with dues or endured through humiliation.

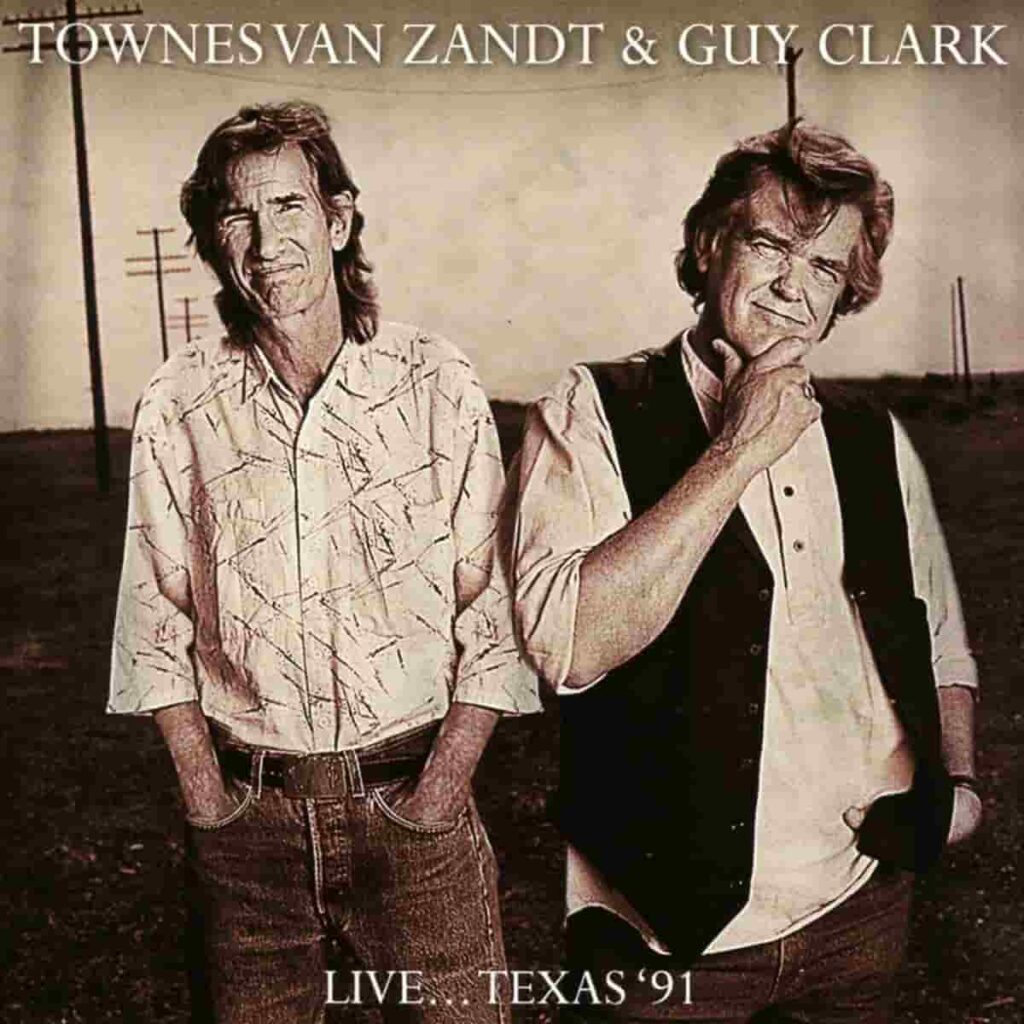

The live recordings where Townes Van Zandt performs the song alongside his close friend Guy Clark give it an even richer texture. Their shared laughter, the subtle interplay of their voices, and the easy way they fall into each other’s timing show the deep camaraderie that defined the Texas songwriting community of the 1970s. These performances are less about showcasing musical virtuosity and more about honoring the old tradition of storytelling. In that sense, the song functions almost like front-porch folklore: a tale told with a wink, where the humor softens the wisdom.

Behind the jokes lies an unmistakable truth familiar to anyone who has lived long enough to know themselves better. “Fraternity Blues” gently exposes the universal moment when a person realizes they do not need to force themselves into spaces where they don’t naturally belong. That realization, humorous as it may be, is profoundly liberating. Older listeners often find themselves smiling at the memory of their own youthful attempts at fitting in, remembering the awkward clubs, the uncomfortable friendships, or the social ladders that ultimately led nowhere. Van Zandt taps into that shared memory with uncanny ease. His humor is never cruel, never mocking others. It is the humor of someone laughing gently at his younger self, acknowledging both the innocence and the mistake.

The song’s emotional resonance also comes from the contrast between its lighthearted surface and Van Zandt’s broader body of work. Known primarily for songs threaded with sorrow and introspection, he reveals here another side of his craft. This humor, dry and understated, is part of what made his concerts unforgettable. Listeners didn’t just admire his poetry; they felt invited into a private circle of friends. And when Guy Clark joined him, the bond between them turned the stage into a gathering place where laughter, wisdom, and memory all intertwined.

In the end, “Fraternity Blues” stands as a reminder that even small, humorous songs can carry meaningful reflections. It invites us to look back on the younger versions of ourselves with kindness, to appreciate the detours of youth, and to recognize that the best parts of life often come not from fitting in but from finding those rare people who laugh with us, sing with us, and understand us just as we are.