An Anthem for the Outlier and the Call of the Wild Heart

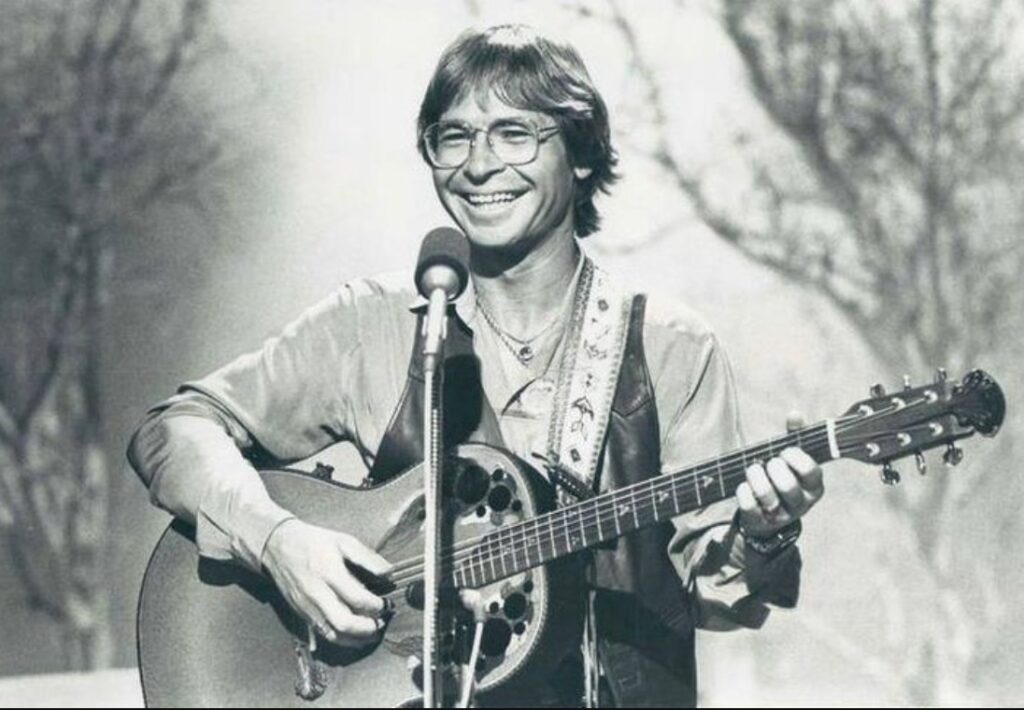

For those of us who came of age during the gentle, earth-conscious 1970s, the music of John Denver holds a sacred, sun-drenched place in our memory. His voice, clear as a mountain spring, often delivered messages that resonated deeply with a desire for simplicity, authenticity, and a connection to the natural world. Among his repertoire, a song that perhaps most poignantly captures this spirit, though not a John Denver original, is the stirring and reflective “Boy from the Country.”

Interestingly, “Boy from the Country” was written by his good friend, Michael Martin Murphey, who had a parallel career exploring themes of the West and nature. Denver recorded it for his landmark 1975 live album, An Evening with John Denver, which captured the pure, magnetic energy of his concerts. While it wasn’t released as a separate single and therefore did not secure a distinct chart position of its own, the album from which it came—An Evening with John Denver—was a colossal success, soaring to Number 2 on the Billboard 200 chart in the US, demonstrating the immense popularity and reach of the material contained within. This live setting, far more than a studio track ever could, allowed the song’s narrative power to truly unfold and connect with the millions who bought the record and saw him on tour.

The song is, at its core, a beautiful and melancholic parable about a profound misfit and a visionary. It tells the story of an individual so deeply intertwined with the rhythms of nature—who speaks to the fish in the creek, who calls the forest “Brother,” and the Earth his mother—that he is perceived as an oddity, perhaps even “insane,” by the conventional, materialist society that surrounds him. The townsfolk, unable to comprehend this primal connection, “drove him out into the rain.”

The ultimate meaning is a gentle, yet firm, critique of modern society’s alienation from nature. The “Boy” is ultimately the only one who truly “sees,” because he “doesn’t want to see the forest for the trees.” This phrase, which is usually meant to critique a person who misses the larger picture, is cleverly inverted here; the boy doesn’t miss the beauty of the forest because he’s distracted by the individual trees, but rather he sees the holistic picture, seeing both the trees and the forest as one interconnected entity. The message is one of unheeded wisdom; the boy tried to tell us “that we should love the land,” but we “just turned our heads and laughed… we did not understand.”

For those of us who heard it back then, this track was more than just a song; it was a rallying cry. It spoke to the nascent environmental movement and affirmed the quiet sense of rightness in prioritizing the environment over endless progress. It was an echo of our own inner voice, a longing for a simpler, more meaningful existence far from the concrete and clamor of city life. The warmth and vulnerability John Denver brought to Murphey’s words made the outcast boy’s story our own, reminding us of the cost of sacrificing our soul’s connection to the land. It remains a timeless reminder that sometimes, the only way to be truly sane is to be perceived as a little “insane” by a world that has lost its way.